Elusive creatures in fossil wood –

Clean-up

in the wake of a

waning obsession

Since about two decades ago, reports on

sightings of oribatid mite coprolites in Carboniferous, Permian, and

Triassic wood appeared and became increasingly popular with time in

some

part of the palaeobotany community although the mites themselves

remained unseen.

Publications by R. Rößler,

including a monograph [1], are a veritable

repository of alleged mite coprolites, as pointed out before (Fossil

Wood News 12).

Neither the absence of mites nor the peculiar

facts that the sizes of

the alleged coprolites always agreed with those of the cells of nearby

tissue, and that often the shapes were angular like the cells [2], gave

rise to suspicion. Local damage to the tissue was interpreted as frass

galleries even if the cavities were so narrow that no mite producing

the

cell-size clots could have

crept there.  Nobody wondered

about how the clots called

coprolites could have got into intact cells, where they are seen more

often than not. (Fossil

Wood News 3,

5)

Nobody wondered

about how the clots called

coprolites could have got into intact cells, where they are seen more

often than not. (Fossil

Wood News 3,

5)

The mite coprolite hypothesis has never been doubted in the scientific

literature, and it proliferated by uncritical adoption. Own efforts

with the aim to spread critical arguments had the effect that some

authors do not speak about mite coprolites any more. Not so R.

Rößler

[3,5]

and Z. Feng

[4,5], who seemed to have had a common interest in keeping up

the coprolite fancy and evading any discussion on the subject. This

resulted in the contributions Fossil

Wood News 4,

5 and a writ by Rößler's

lawyer declaring the mite coprolite hypothesis

the state of science. While

others have quietly dropped the idea, Rößler

and Feng

seem to be resolved to stick to it but they made the concession

to abandon the "oribatid mites"

and replace them by

"unknown

creatures" [3] or "new

detritivores" [5]*. These

are terms thought up in vain since the clots cannot be coprolites,

which meanwhile has been demonstrated with numerous examples (Fossil

Wood News 7).

What is left over from the

subsided oribatid mite coprolite craze is its

debris in the palaeobotany literature. The

professionals who spread it

are not inclined to clean up. The much praised ability of science to

correct itself has got lost in parts of palaeobotany. Hence,

weeding out the errors and misconceptions must be done by

outsiders. A few more examples are presented here.

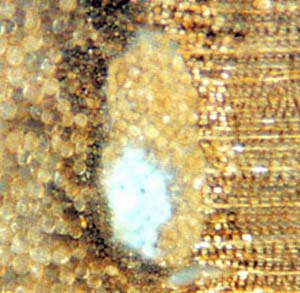

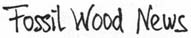

Fig. 1: Detail from [1], Bild 441, described there as a tunnel eaten

into coniferous wood, filled with coprolites.

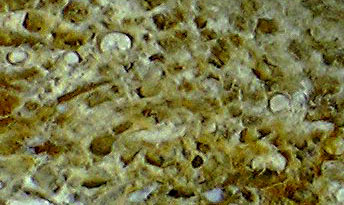

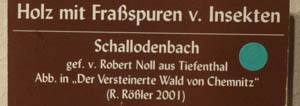

Fig.2 (right): Coniferous-type wood cells squeezed into an

imperfect honeycomb structure by bloating apparently due to some

expanding matter inside.

Detail from [4], Fig.6E, interpreted as oribatid mite

coprolites there.

Doubts

concerning coprolites in Fig.1 are raised by the observation that the

clots are densely packed and of various sizes and shapes, on the

average slightly bigger than the wood cells on the right and slightly

smaller than the pith cells on the left. Comparison with similar

structures (Fig.2) suggests that they are bloated and slightly

displaced wood cells, filled with some light-coloured matter, as

explained in Fossil

Wood News 5.

Similar

phenomena are pictured

in [6] and Fossil

Wood News 21,

Fig.7 there.

Similar

phenomena are pictured

in [6] and Fossil

Wood News 21,

Fig.7 there.

Fig.3 (right): Expanded tissue inside a cavity in silicified wood (Fossil

Wood News 14).

Width of the cavity 2mm.

There are more examples of cavity formation in wood in

combination with the bloating of cells (Fig.3).

All that can be said here about the wood damage in Figs.1-3

is that there is some obscure connection with expanding cells but no

connection with tunnel-boring creatures. The obsession of some authors

with alleged

arthropod

traces in fossil wood had apparently misled them to the assumption that

the furrows in the Lower Permian fossil wood in Fig.4 are burrows. As

seen already on the image, the furrows have V-shaped cross-sections,

often with a thin line along the bottom. Such furrows cannot be

burrows.

Fig.4: Alleged arthropod burrows on the surface of Permian

wood,

after Rößler,

detail of Bild 442 in [1], there with wrong scale. Width of Fig.4 as

measured on the sample: 14cm. The furrows must be shrinkage cracks

formed during silicification, later widened by spalling

fracture

on the crack edges: no burrows.

(New picture and desctiption: Fossil

Wood News 29.)

Fossil

Wood News 29.)

Label to the sample of Fig.4,

Paläontologisches Museum Nierstein

According to the scale 4:1 in [1] the size

of Fig.4 would be 1cm,

which is highly questionable. A check at the Paläontologisches

Museum Nierstein gave 14cm. Close

inspection of the sample confirmed the conclusions already derived from

the image: The wide furrows developed from narrow shrinkage cracks.

Repeated impact of river pebbles caused spalling fracture at the crack

edges, which created cross-sections with V-shape in the depth and

rounded edges above. The original narrow crack, which may be filled

owing to later silicification, is seen within some furrows as a thin

dark

line along the bottom, eventually with a tiny

ridge left over from the broken away narrow crack fill. Needless

to

say that a boring creature could never make grooves of such peculiar

shape.

Shrinkage crack formation during silicification

is a common phenomenon. There are conspicuous examples in Permian wood

from the Döhlen Basin.

Fig.4

has

been turned here such that the light comes from above left which makes

a better 3D-impression.

By the way, Bild 442

in [4] is the mirror image of the object, and so is Fig.4. This

information may be useful for comparison with the sample.

Fig.4

has

been turned here such that the light comes from above left which makes

a better 3D-impression.

By the way, Bild 442

in [4] is the mirror image of the object, and so is Fig.4. This

information may be useful for comparison with the sample.

Fig.5 (right): Galleries with U-shaped cross-sections without crack

along

the bottom, and

cracks on the surface of a fossil tree trunk

from Chemnitz. Detail of Fig.5 in [7]. Width of the picture 7.5cm.

Burrows

and galleries below the bark would be U-shaped and without a narrow

crack along the

bottom, like those shown in Fig.5

for comparison.

As a big surprise after so much vain talk about mite coprolites without

mites we may have fossil mites without coprolites now.

Gert

Müller

seems to have got the elusive mites in their

burrows in plant tissue preserved in chert

(Fig.6) [8]. As expected, none of the popular "coprolites" are seen

there.

Fig.6:

Juvenile arthropods in burrows in degraded tree fern tissue in Lower

Permian chert, Freital, Döhlen

basin,

Saxony.

Width of the picture about 3mm. Sample and photograph by Gert

Müller.

Amendment 2015:

After having avoided the disputed term

"oribatid mite coprolites" for some time, R. Rößler has

made use of it again recently [9,10] despite of plain evidence proving

it ill-conceived: see Fossil

Wood News 23,

24.

H.-J.

Weiss

2012, updated 2013, 2014, 2015, 2019

[1] R. Rößler:

Der versteinerte Wald von Chemnitz. Museum f. Naturkunde Chemnitz 2001

[2] H.-J. Weiss:

Milbenfraß und Milbenkot, 6th Chert Workshop, Naturkunde Museum

Chemnitz, 2007.

[3] M. Barthel,

M.

Krings, R. Rößler: Die schwarzen Psaronien von Manebach,

ihre Epiphyten,

Parasiten und Pilze.

Semana 25(2010), 41-60. (

recently re-named, former name: Veröff.

Naturhist. Mus. Schleusingen)

[4] Zhuo

Feng,

Jun Wang, Lu-Yun Liu: First report of oribatid mite

(arthropod) borings and coprolites in Permian woods from ... northern

China.

Palaeogeography,

Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 288(2010), 54-61.

[5] Zhuo Feng,

Jun Wang, Lu-Yun Liu, Ronny Rößler: A novel coniferous

tree trunk with septate pith ...

Int. J. Plant Sci. 173(2012),

835-48.

[6] H.-J. Weiss:

Beobachtungen an Kieselhölzern des Kyffhäuser-Gebirges.

Veröff. Mus.

Naturkunde Chemnitz 21(1998), 37-48.

[7] R. Rößler,

G. Fiedler:

Fraßspuren an permischen Gymnospermen-Kieselhölzern ...

Veröff. Mus. Naturkunde

Chemnitz 19(1996), 27-34.

[8] G. Müller:

private communication.

[9] R.

Rößler, R. Kretzschmar, Z. Feng, R. Noll: Fraßgalerien von

Mikroarthropoden in Konifernhölzern des frühen Perms von Crock,

Thüringen.

Veröff. Mus.

Naturkunde Chemnitz 37(2014), 55-66.

[10] Zhuo

Feng,

J.W. Schneider, C.C.

Labandeira, R. Kretzschmar, R.

Rößler: A specialized feeding habit of Early

Permian oribatid mites.

Palaeogeography,

Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 417(2015), 121-124.

|

|

16 16 |

16

16 Nobody wondered

about how the clots called

coprolites could have got into intact cells, where they are seen more

often than not. (Fossil

Wood News 3,

5)

Nobody wondered

about how the clots called

coprolites could have got into intact cells, where they are seen more

often than not. (Fossil

Wood News 3,

5)

Similar

phenomena are pictured

in [6] and Fossil

Wood News 21,

Fig.7 there.

Similar

phenomena are pictured

in [6] and Fossil

Wood News 21,

Fig.7 there.

Fossil

Wood News 29.)

Fossil

Wood News 29.) Fig.4

has

been turned here such that the light comes from above left which makes

a better 3D-impression.

By the way, Bild 442

in [4] is the mirror image of the object, and so is Fig.4. This

information may be useful for comparison with the sample.

Fig.4

has

been turned here such that the light comes from above left which makes

a better 3D-impression.

By the way, Bild 442

in [4] is the mirror image of the object, and so is Fig.4. This

information may be useful for comparison with the sample.

16

16