Dubious oribatid mite coprolites once more: Comment on Z.

Feng

et al. (2010)

Lately, not much was heard about oribatid mite coprolites, a favourite

topic in palaeobotany a few years ago. (See chapter

Misconceptions.)

So the recent paper by Feng

on this subject [1] came

unexpected. Unfortunately, it does not fulfill the expectations raised

by its title.

A brief look at the photographs of dark clots in silicified wood

reveals that most of them are no coprolites. Although the subject had

been discussed in detail in connection with previous papers on alleged

mite coprolites so that one might expect the matter settled, it has to

be considered here anew, with the same old and simple but adequate

reasoning applied to the new pictures provided in [1].

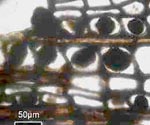

There are several conspicuous details in the pictures which should

raise suspicion even with unexperienced observers. One such detail is

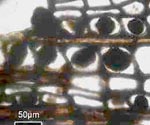

the presence of clots with distinctly angular shape (Figs.1...4).

Furthermore, the shapes and sizes of the clots often agree with the

shapes and sizes of nearby cells, as observed before on fossil wood

from Antarctica.

Figs. 1...4: Clots in silicified Permian wood, interpreted

as mite coprolites in [1] despite of their angular shapes; details from

[1], there in Figs. 3I, 4E, 3C, 3I (left to right).

Among the numerous clots in the samples there are often

a few ones in positions which seem awkward from a coprolite point of

view: They are seen deep inside tracheids where no mite could have

crept in. The deceptively plausible explanation offered by the

proponents of the coprolite hypothesis that they simply fell into the

tracheid at an open end is not a good one: In some cases the clots are

seen in several neighbouring tracheid cross-sections (Figs. 5...7), so

while falling in they all would have got stuck at the same depth. By

the way, things as small as mite droppings would not easily tumble down

tubes of about the same diameter since their weight is usually

negligible compared to adhesion forces, especially if traces of

moisture are present. They would just stick to the wall but not slide

down.

The arrangement of the clots in the below pictures suggests quite

another explanation: They have been formed inside the cells. The two

tiny clots in neighbouring cells in Fig.6 are possibly early stages of

clot formation. As a significant feature also observed with samples

from elsewhere, the clots are not randomly

distributed among the cells but tend to cluster.

In other words, a cell

with clot is more likely to have got a neighbouring cell with clot than

to have not. This supports the previously proposed idea of a fungus

infection

spreading from one cell to another as the cause of clot formation

[2,3]. A phenomenon of this kind, a clot sending a hypha through the

cell wall to make another clot in the neighbouring cell, is seen in a

remarkable photograph in [4].

Some of the clots eventually keep their position even after the cell

walls have decayed, as three clots in a row in Fig.5, and less clearly

seen in Fig.6. The most convincing evidence for clot formation in cells

is provided by Fig.7, with three and four clots in a row, sitting at

the same height in neighbouring tracheids. Note also the two smaller

clots in smaller cells below, one above the scale bar and another one

on the right. Some of the clots look as if their shapes were tapering

towards a site of attachment to the cell wall.

Figs.

5...7: Clots in silicified Permian wood, interpreted as mite coprolites

in [1] despite of their peculiar arrangement suggesting their formation

inside cells; details from [1], there in Figs. 4B, 4B, 4F (left to

right).

Figs.

5...7: Clots in silicified Permian wood, interpreted as mite coprolites

in [1] despite of their peculiar arrangement suggesting their formation

inside cells; details from [1], there in Figs. 4B, 4B, 4F (left to

right).

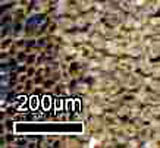

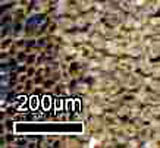

A

formation in silicified wood with not really clot-like aspect

(Figs.8...10) is also interpreted as oribatid mite coprolites in [1].

There are patches on the petrified wood cross-section where the usual

wood structure with cells in radial files (vertical in Figs.8 and 10)

is replaced by something resembling an imperfect honeycomb structure.

Figs.

8...10: Silicified Permian wood affected by what appears to be some

kind of wood rot, interpreted as mite coprolites in [1] despite of the

polygonal shape of the elements and their dense-packed honeycomb-like

arrangement; details from [1], there in Fig. 6E.

Figs.

8...10: Silicified Permian wood affected by what appears to be some

kind of wood rot, interpreted as mite coprolites in [1] despite of the

polygonal shape of the elements and their dense-packed honeycomb-like

arrangement; details from [1], there in Fig. 6E.

As seen in

Figs. 8 and 10, the light-coloured area adjoins the unaffected wood

whose cells appear dark as they were hollow before silicification and

are now filled with clear chalcedony so that one can look into the dark

depth. The two light-coloured elements below the empty cells in Fig.10

fit into the cell pattern seen above. So they must be cells filled with

some substance.

In order to interpret the alleged coprolites in

Figs. 8 and 9 as modified cells, it must be explained why they are not

arranged in files and seem to be slightly larger than the cells. As a

possible explanation, the cells may have been affected by wood rot

caused by some fungus or microbe which feeds on the cell wall and

produces organic matter inside the cells, be it a dense tangle of tiny

hyphae (as in Rhynie chert plants [4], see also Fossil

Wood News 4, Rhynie Chert News 28 ) or microbial debris. Judging

from Fig.8 where several of the affected cells seem to be not

completely filled, the matter forms along the walls first. The fill of

the affected cells apparently expands, and since the cell walls are

weakened by the fungi or microbes feeding on them, they do not keep the

original shape. So by mutual squeezing of the expanding cells, or

rather their fills, an imperfect honeycomb structure is brought about.

Such

type of decay of the wood structure is not uncommon in Palaeozoic wood.

Bloating of affected cells and dissolution of the radial files has been

described with wood from the Kyffhäuser mountains, Germany, and

elsewhere [5]. Light-coloured cell-size clots beside dark ones are seen

in Lower Permian wood from Schallodenbach, Germany.

Most probably,

the cell-size clots of various aspect will reveal something interesting

in the future but the favourite interpretation as oribatid mite

coprolites will become a memorable folly of the past.

H.-J. Weiss

2010

[1] Zhuo

Feng,

Jun Wang, Lu-Yun Liu :

First report of oribatid mite (arthropod) borings and coprolites in

Permian woods from the Helan Mountains of

northern China.

Palaeogeography,

Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 288(2010), 54-61.

[2] H.-J. Weiss ,

6. Chert Workshop 2007, Naturkunde-Museum Chemnitz.

[3] H.-J. Weiss ,

7. Chert Workshop 2008, Naturkunde-Museum Chemnitz.

[4] T.N. Taylor,

E.L. Taylor, M. Krings : Paleobotany,

Elsevier 2009, Fig. 3.96

[5] H.-J. Weiss :

Beobachtungen an Kieselhölzern des Kyffhäuser-Gebirges.

Veröff. Mus.

Naturkunde Chemnitz 21(1998), 37-48.

|

|

5 5 |

5

5

Figs.

5...7: Clots in silicified Permian wood, interpreted as mite coprolites

in [1] despite of their peculiar arrangement suggesting their formation

inside cells; details from [1], there in Figs. 4B, 4B, 4F (left to

right).

Figs.

5...7: Clots in silicified Permian wood, interpreted as mite coprolites

in [1] despite of their peculiar arrangement suggesting their formation

inside cells; details from [1], there in Figs. 4B, 4B, 4F (left to

right).

Figs.

8...10: Silicified Permian wood affected by what appears to be some

kind of wood rot, interpreted as mite coprolites in [1] despite of the

polygonal shape of the elements and their dense-packed honeycomb-like

arrangement; details from [1], there in Fig. 6E.

Figs.

8...10: Silicified Permian wood affected by what appears to be some

kind of wood rot, interpreted as mite coprolites in [1] despite of the

polygonal shape of the elements and their dense-packed honeycomb-like

arrangement; details from [1], there in Fig. 6E.

5

5