Oribatid mite coprolite sightings – a

transient craze ?

Petrified wood does not only preserve the tissue structure of wood from

bygone times but occasionally also its pests. Small wonder that

irregular-shaped tiny holes in the wood with dark clots inside are

interpreted as mites’ burrows with coprolites. Leaving the question

aside whether the clots in some samples are really what they are

believed to be, a very few observations make that interpretation highly

dubious.

Nevertheless the oribatid mites, or rather their coprolites, became

increasingly popular among palaeontologists in the 1990s. I did not try

to find out when and where it started. The first dubious coprolite

images which came to my notice were Fig.1 and Fig.2.

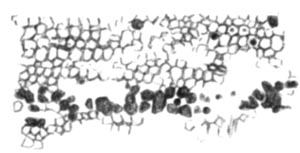

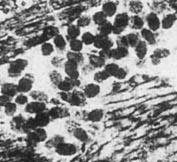

Fig.1: Silicified wood from the Wetterau area (Permian), Germany; cross

section with local damage thought to be caused by mites in [1]. A few

intact wood cells with clot inside (above right) raise doubts

concerning the coprolite hypothesis. Drawing after

photograph in [1].

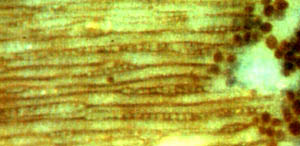

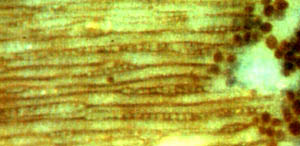

Fig.2 (right): Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian),

Germany;

longitudinal section with local damage thought to be caused by mites in

[2]. The individual small clot deep inside a tracheid raises doubts

concerning the

coprolite hypothesis. Detail of photograph in [2].

Close

inspection of the pictures raises

doubts as one can see individual clots within intact wood cells where

they

hardly could have been dropped by mites. The doubts concerning mite

frass are

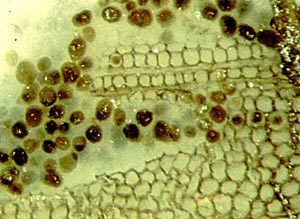

confirmed by another sample (Fig.3), where clots are seen in three

cells in a

row. Accepting the coprolite hypothesis would imply that three tiny

mites had

crept along neighbouring tracheids and deposited their droppings at

exactly the

same height.

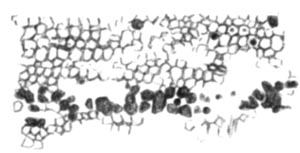

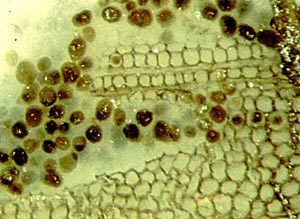

Fig.3: Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian), Germany,

cross section with local damage. Three intact wood cells in a row with

clot inside may serve as evidence against the coprolite hypothesis.

Own sample, kindly provided by Ch. Krüger ,

Schallodenbach.

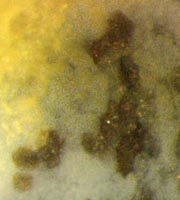

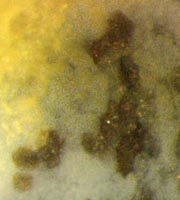

In addition to the more or less rounded clots formed in the xylem

cells, the sample of Fig.3 contains also distinctly angular clots

formed in the larger pith cells (Fig. 4). Clots with angular shape

should serve as convincing evidence against the interpretation as

coprolites.

Fig.4

(right):

Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian), Germany, same

sample as Fig.3, cross section of pith cavity in coniferous-type stem

with only those pith cells preserved in outline which are filled with

dark matter.

Fig.4

(right):

Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian), Germany, same

sample as Fig.3, cross section of pith cavity in coniferous-type stem

with only those pith cells preserved in outline which are filled with

dark matter.

Nevertheless, the idea of discovering mite coprolites in one's fossil

plant

samples seemed to be so tempting to some palaeontologists that it

spread worldwide, even to Antarctica [3]. Apparently not even the fact

that oribatid mite fossils were absent in the Carboniferous, Permian,

and Triassic where the alleged coprolites were most abundant [4] could

dampen the eagerness with which the idea was accepted without being

checked against common sense. Hence, sightings of oribatid mite

coprolites were soon reported from samples stored at the

Naturkunde-Museum Chemnitz [5-8]. About a century ago, the angular

clots within plant tissue, including those in Fig.5, had probably been

noticed by the clever J.T.

Sterzel (1841-1914)

who was cautious enough not to propose an interpretation.

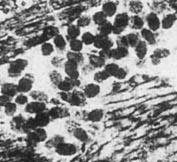

Fig.5: Angular clots in the tissue of the Permian climbing fern

Ankyropteris brongniartii,

recently interpreted as mite coprolites

[5-7].

Sample Nr. K 4568, stored at the Museum für Naturkunde Chemnitz

since Sterzel's

time.

In view of the fossil evidence the following can be stated: Clots

confined to the interior of intact cells (Figs.1-4) and angular

clots with sizes and shapes like the cells of the damaged tissue

harbouring

them (Figs.4,5) cannot be interpreted as coprolites. Although the

tell-tale shape and size is more or less evident from pictures in

several publications, the authors apparently did not consider this

worth mentioning.

The pictures most probably show a kind of wood rot caused by a fungus

as

explained in Rhynie

Chert News 28.

From 2007 on when

fossil oribatid mite coprolites were still a favourite topic among

palaeontologists, this alternative

interpretation had been sent to the authors listed below. It is hoped

that

such spread of information, together with the message conveyed by this

essay, will help to make the craze of

oribatid mite coprolite sightings, as well as other misconceptions,

fade away and vanish.

See also the special contribution "Antarctic shit".

H.-J.

Weiss

2010

[1] K.

Goth, V. Wilde : Fraßspuren in permischen

Hölzern aus der Wetterau,

Senckenbergiana letaea 72(1992), 1-6.

[2] R.

Noll, V. Wilde : Conifers from the „Uplands“

– Petrified wood from Central Germany,

in:

U. Dernbach, W.D. Tidwell : Secrets of Petrified Plants,

D'ORO

Publ., 2002.

[3] D.W.

Kellog, E.L. Taylor : Evidence of oribatid mite

detrivory in Antarctica during the Late Paleozoic and Mesozoic,

J. of Paleontology 78(2004), 1146-53.

[4] C.C.Labandeira,

T.L. Phillips, R.A. Norton : Oribatid

mites and the decomposition of plant tissues in paleozoic coal swamp

forests,

Palaios 12(1997), 319-53.

[5] R.

Rössler : The late palaeozoic tree fern

Psaronius - an ecosystem unto itself,

Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn. 108(2000), 55-74.

[6] R.

Rössler : Der versteinerte Wald von Chemnitz, 2001, p

141,155,169.

[7] R.

Rössler : Between precious inheritance and immediate

experience,

in: U. Dernbach, W.D. Tidwell

: Secrets

of Petrified Plants, D'ORO Publ., 2002.

[8] R.

Rössler: Two remarkable Permian petrified forests,

Geol. Soc. London Special Publ.

265(2006), 39-63.

|

|

3 3 |

3

3

Fig.4

(right):

Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian), Germany, same

sample as Fig.3, cross section of pith cavity in coniferous-type stem

with only those pith cells preserved in outline which are filled with

dark matter.

Fig.4

(right):

Silicified wood from Schallodenbach (Lower Permian), Germany, same

sample as Fig.3, cross section of pith cavity in coniferous-type stem

with only those pith cells preserved in outline which are filled with

dark matter.

3

3