Microbes, fungi, maggot fern

Fungi

are supposed to have been around since the Proterozoic [1] but have

been preserved as fossils only under conditions of rapid

silicification, as in the Lower Devonian habitat turned into the Rhynie

chert

with lots of well-preserved fungus remains. Fossil fungi are rare in

the Permian cherts of the Döhlen basin.

(See Permian

Chert News 14.)

Perhaps some hyphae are easily

overlooked if poorly preserved, or they are mistaken for microbial

filaments or plant hairs.

Fungi

are supposed to have been around since the Proterozoic [1] but have

been preserved as fossils only under conditions of rapid

silicification, as in the Lower Devonian habitat turned into the Rhynie

chert

with lots of well-preserved fungus remains. Fossil fungi are rare in

the Permian cherts of the Döhlen basin.

(See Permian

Chert News 14.)

Perhaps some hyphae are easily

overlooked if poorly preserved, or they are mistaken for microbial

filaments or plant hairs.

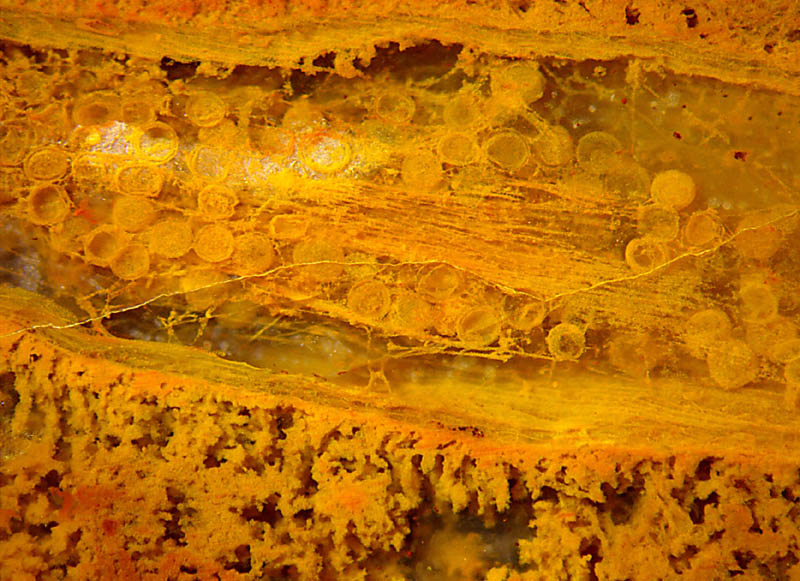

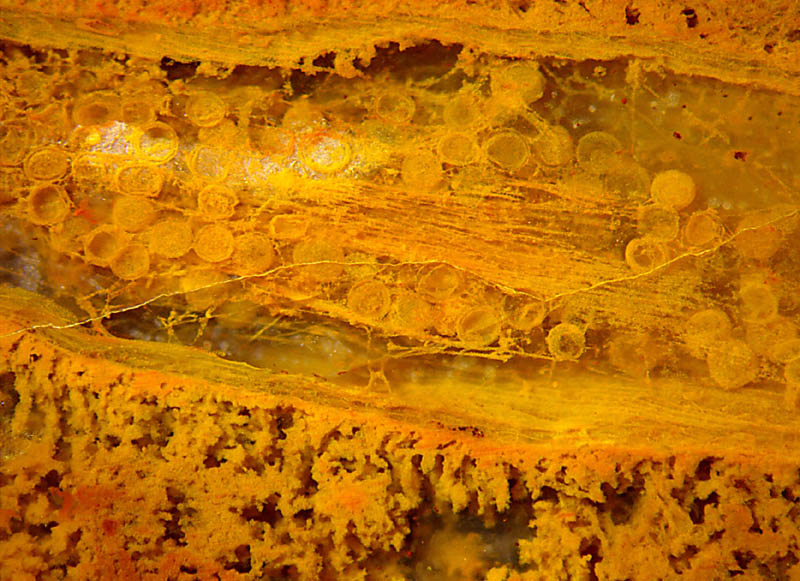

Fig.1: Curved pinnules of the "maggot fern" (Scolecopteris)

in a row, cut such that the cross-sections with sporangia and the

sheltered spaces with thin hyphae and thicker hairs are seen. Width of

the image 8mm.

A rare combination of microbes, fungus hyphae, and plant hairs is seen

in

Fig.1, which shows an inclined cut of a row of curved maggot fern

pinnules. Apparently these pinnules are even more curved than those

seen in side view in Permian

Chert News 1.

Owing to the

curvature, the pinnules appear nearly as

cross-sections above (see Permian

Chert News 15)

and provide a look into the sheltered space between the fringes of the

lamina below.

The pale empty sporangia of the fern may be easily recognized as such.

The thin fungus hyphae are easily seen against the dark background if

not

covered with microbes too much. The hairs sparsely distributed at the

lower side of the pinnules are much thicker than the hyphae (Fig.2).

Fig.2:

Detail from Fig.1, near image centre, hair emerging from the lamina of

the pinnule, with thin fluffy microbial cover, glistening spot where

the

cover probably had been scratched off before silicification so that the

smooth reflecting surface appeared. Image width 0.7mm, lamina thickness

0.25mm.

The microbes involved here do not form filaments by

themselves but coatings and

floccules without definite shape but with sharp boundaries against the

surrounding water.

The

yellow, red, and brown colours are provided, as usual, by iron oxides.

The bluish hue on the left of Fig.1 is not due to a mineral pigment but

to light scattered on tiny precipitates in the clear chalzedony.

Fig.3:

Slightly inclined lengthwise section of a largely decayed root

surrounded by a thick fluffy microbial coating and with numerous

spherical chlamydospores of some fungus with a few thin hyphae standing

out

against the dark background. Width of the image 5mm.

Like

hyphae, chlamydospores are seldom seen in Permian cherts but are common

fossils in the Rhynie chert. (See Rhynie

Chert News 104, 115.)

The large bunch of parallel filaments is the decayed central strand

The assemblage of numerous chlamydospores

in Fig.3 is the only find of this type in the Permian

cherts of the Döhlen basin but similar

assemblages are known from the Rhynie chert. Diameters

of the spheres in Fig.3 are up to 0.3mm, thus being comparable to those

in 104

.

No attempt has been made here to assign

these finds to a certain

fungus clade.

Another problem remains: Why did this fungus, which is a tangle of thin

hyphae,

choose to produce bulky chlamydospores in large numbers and to

place them clustered together ? One may assume that there must be a

reason which has to be found out.

It may be appropriate here to

warn against a potential misinterpretation: Spherulites must not be

mistaken for chlamydospores. Two of such, size 0.34mm, are half seen in

Fig.1 between the first and second pinnule.

Samples: Döhlen basin, Hänichen, Käferberg.

Figs.1,2: H/321.1, 0.85kg, 1999,

Fig.3: H/333.2, 4.65kg, 2001.

[1] T.N.Taylor, M.

Krings, E.L. Taylor: Fossil Fungi. Elsevier 2015, p.28.

H.-J.

Weiss

2017

|

|

17 17 |

17

17 Fungi

are supposed to have been around since the Proterozoic [1] but have

been preserved as fossils only under conditions of rapid

silicification, as in the Lower Devonian habitat turned into the Rhynie

chert

with lots of well-preserved fungus remains. Fossil fungi are rare in

the Permian cherts of the Döhlen basin.

(See Permian

Chert News 14.)

Perhaps some hyphae are easily

overlooked if poorly preserved, or they are mistaken for microbial

filaments or plant hairs.

Fungi

are supposed to have been around since the Proterozoic [1] but have

been preserved as fossils only under conditions of rapid

silicification, as in the Lower Devonian habitat turned into the Rhynie

chert

with lots of well-preserved fungus remains. Fossil fungi are rare in

the Permian cherts of the Döhlen basin.

(See Permian

Chert News 14.)

Perhaps some hyphae are easily

overlooked if poorly preserved, or they are mistaken for microbial

filaments or plant hairs.

17

17