Fungi in Permian chert

For variuos reasons, fossil fungi

are rare despite of the fact that they had been helpful to plants when

they occupied the dry land in the Silurian and Devonian [1].

As an exception, the Rhynie Chert (Lower Devonian) is famous among

biologists for the excellent preservation of hyphae and

"chlamydospores" of several fungi.

Only

a few of the expected numerous palaeozoic fungus species have been

found well preserved in chert, and only part of them have been

scientifically described. Some lived as symbionts or parasites, others

lived on decaying dead plant tissue, also in the swamp water where they

occasionally formed extended tangles of branching hyphae. With

silica-rich swamp water turning into gel and finally into chert, the

hyphae became silicified.

Cherts from Germany

have yielded very few fungi. It can be expected that some of the

numerous chert samples recovered from Döhlen basin (Lower

Permian), superficially or not yet

inspected hitherto, will provide a few more specimens. Hyphae within

quartz crystals (Tertiary) have been found near Warstein [2].

A

peculiar fact may be mentioned here: A particular kind of wood rot with

hyphae filling the wood cells with profusely branched "arbuscules" has

been described by several palaeobotanists, with increasing zeal, as

oribatid mite coprolites in petrified wood.

(See Rot

or "coprolites" and Research gone astray.)

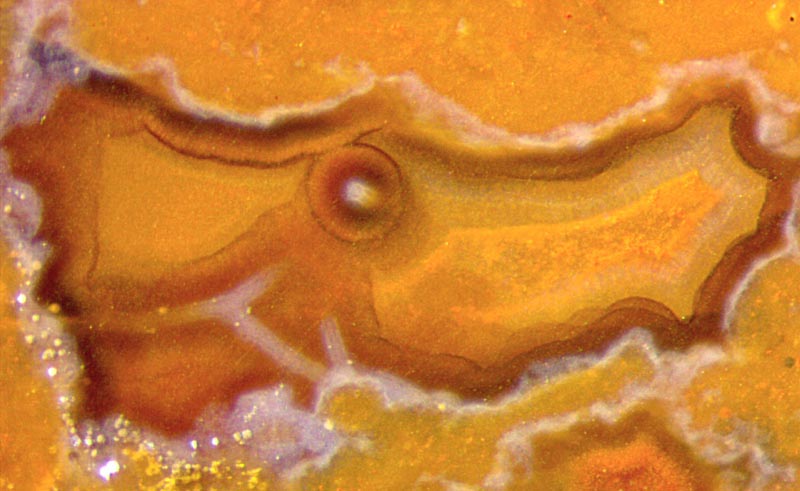

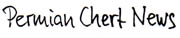

Fig.1:

Chalzedony, formerly water-filled cavity with poorly visible fungus

hyphae, diameter <10µm, with pale coating, about 25µm, and brown

coating, 170µm. Picture width 1.4mm.

Fig.1:

Chalzedony, formerly water-filled cavity with poorly visible fungus

hyphae, diameter <10µm, with pale coating, about 25µm, and brown

coating, 170µm. Picture width 1.4mm.

The lower pH inside decaying plant parts in

silica-rich water favours silica gel formation

there first. Subsequently, coatings may be formed.

Fungus hyphae often thrive in the remaining water-filled cavities. They

become coated with silica gel, eventually with several layers due to

changing parameters, as temperature. The concentric layers may appear

as pale in clear vicinity or clear in pale vicinity, for example

(Fig.1-3). The coated hyphae may bend down under their own weight.

The subsequent processes

are governed by the supersaturation of the remaining solution: High

supersaturation makes gel and later chalzedony in the whole cavity. Low

supersaturation makes quartz crystals on the coated hyphae and on the

walls. Crystal growth ends when silica does not

enter by

diffusion (not flow !) anymore. Later the water vanishes and the coated

hyphae cross the empty cavity. (See

Rhynie

Chert News 63,

64,)

Coated

needle-shaped crystals and mineral formations like those in moss agate

are liable to being confused with hyphae. Long straight parts ending at

branching sites are absent in moss agates, and curved parts are absent

with crystal needles (Fig.1).

Fig.2,3: Multiply coated fungus hyphae, height of the pictures 0.35mm,

same scale as Fig.1.

Diameters of the coatings in Fig.2 (µm):

10, 14, 22, 28, 40, 48, 110, 125,

145(?).

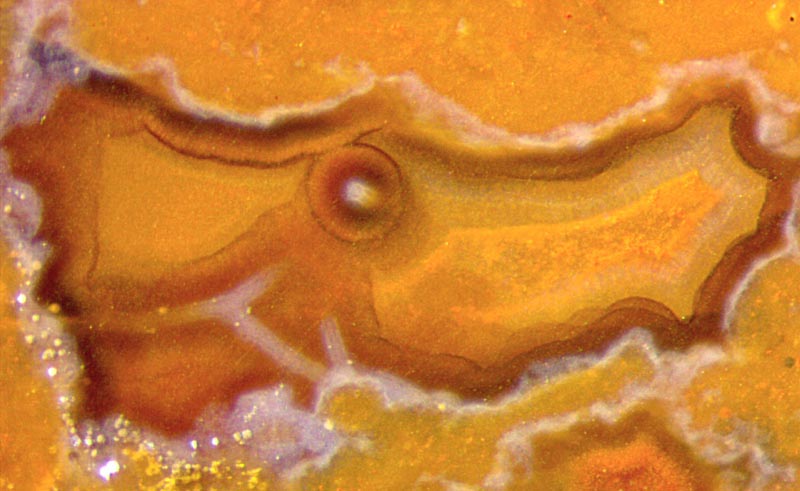

Fig.4

(below): Tree fern frond stalk, largely decayed

and silicified while lying in swamp water, indistinct tangle of poorly

preserved fungus hyphae in some places, 4 (or more)

spherical chlamydospores, cut or transparent, empty, thick

microbial cover (cyanobacteria ?) on the left. Width of the picture

5.5mm.

Fungus hyphae are rare in the cherts of the Döhlen basin.

Probably

they decayed before they became coated with silica gel. The

comparatively

big spherical chlamydospores, which possibly guarantee

survival after decay of the hyphae, are another feature revealing the

presence of fungi. They are not easily seen among the debris in Fig.4.

Here, the wall of the chlamydospores

is apparently not much stained by the abundant yellow or red iron

oxides deposited from soluble iron compounds.

(In Permian cherts, chlamydospores seem to be much less

abundant and less clearly seen than in the Lower Devonian cherts from

Rhynie.)

Samples: Döhlen basin, Lower Permian.

Fig.1-3: Kleinnaundorf,

Kohlenstr., found by

H. Ahlheim;

cut and polished by H. Albrecht, label Bu7/207.

Fig.4: own find, Hänichen, Käferberg; own

collection, label H/333.1 .

H.-J.

Weiss

2015 modified 2017

[1] D. Redecker: New views on fungal evolution based on

DNA markers and the fossil record.

Res. Microbiology 153(2002), 125-130.

[2] M. Kretzschmar: Fossile Pilze in Eisen-Stromatolithen von Warstein.

Facies 7(1982), 237-259.

|

|

14 14 |

14

14 Fig.1:

Chalzedony, formerly water-filled cavity with poorly visible fungus

hyphae, diameter <10µm, with pale coating, about 25µm, and brown

coating, 170µm. Picture width 1.4mm.

Fig.1:

Chalzedony, formerly water-filled cavity with poorly visible fungus

hyphae, diameter <10µm, with pale coating, about 25µm, and brown

coating, 170µm. Picture width 1.4mm.

14

14