Fossiliferous

cherts

Unlike the conspicuous slabs with large compressed fossils

often seen in museums, fossiliferous cherts usually do not make large

fossil exhibits but nevertheless impressive samples if cut and

polished, with life-like three-dimensional

preservation in partially transparent chalcedony, often beautifully

coloured. The preservation of tiny detail even

on the micrometer scale contributes to their

scientific value.

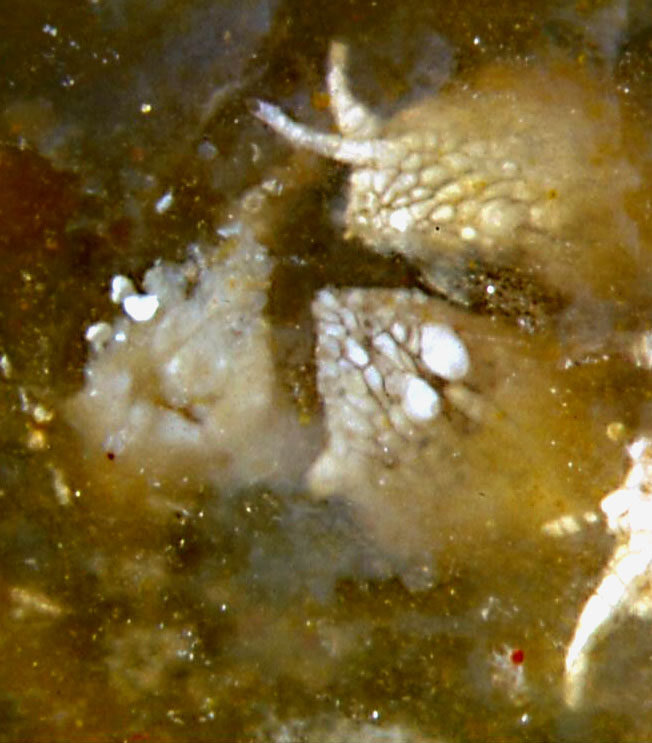

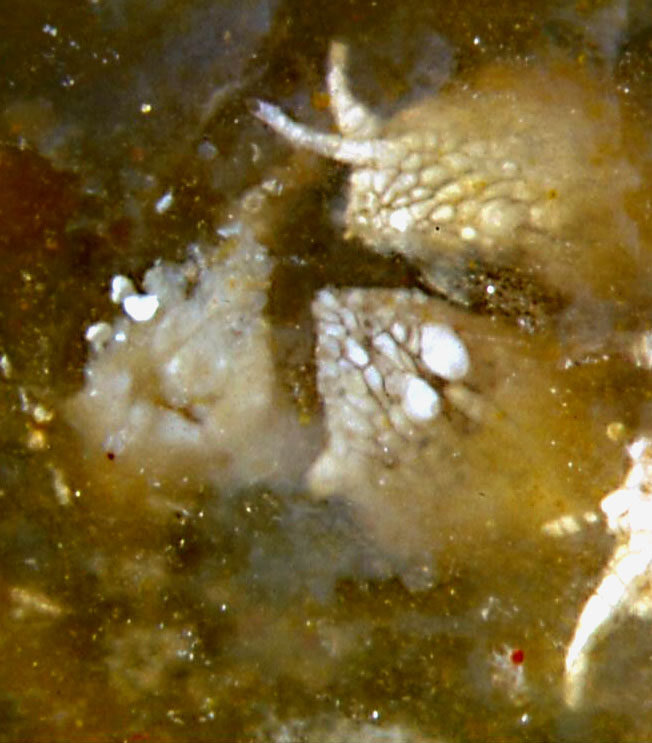

Photograph: Evidence for preservation of tiny detail in transparent

chalcedony. Sporangia of the tree fern Scolecopteris with

clearly seen cells on the surface,

quite uncommon variety with two hairs emerging near the pointed top

of the capsules, (cut off at the lower

sporangium, seen as white spots,) unknown

species ?

Lower Permian, Döhlen basin, Saxony, Germany.

Fossiliferous cherts have not received due attention as they

are most often found as pebbles in gravel pits and

fluvial deposits and along rivers but

rarely as outcrops, which makes them unsuitable for stratigraphy.

As an exception to this rule, most of the famous Rhynie chert recovered

hitherto, now stored at museums and universities and not yet fully

investigated, was dug up by

trenching into subcrops of in-situ chert layers [1]. Smaller amounts

have been found scattered in the area, with sizes of a few grams up to

65kg.

Big chert boulders are rare because the layers break into pieces while

being

washed out of the banks and carried along by the river. The width of

the fragments is usually not much larger than the thickness of the

chert

layer. The width can even be smaller if the

brittle layer had been bent by deformation of the stratum where it is

embedded.

The biggest chert boulder from Döhlen

basin is a Lower Permian chert of 31kg with numerous fern frond

fragments, found in a trench in a glazial fluviatile deposit at

Hänichen near Dresden.

The lately increased interest in fossiliferous cherts in

Saxony

has been brought about by lucky incidences: (1) first new find of a

"maggot stone" since 1893 by Gert

Müller in 1985 after purposeful search, (2) essay on the

old "maggot

stone" finds by M.

Barthel

1987 [2], which encouraged the present writer to look for fossiliferous

cherts in a wider area, (3) earthwork and construction pits in

fluviatile deposits with

fossiliferous cherts, since 1991. This interest is held up mainly

by the

activity of non-professionals who are fascinated by the

encounter with ancient life forms but don't care

much about stratigraphy. Ralph Kretzschmar had

created the website www.kieseltorf.de, which enabled

lay fossil collectors and himself to make known their finds and

discoveries. It is

deplorable that this dedicated staff

member at the Naturkunde-Museum

Chemnitz, who had advanced from self-taught paleontologist to the

supervisor of excavations, suddeny quit his job, deleted his website,

and turned away

from paleontology in 2017. (In this connection, Fossil Wood

News 16 may

be revealing.)

It is strongly emphasized that the field work of collecting

fossiliferous

cherts differs much from searching for and recovering compression

fossils in sediment rocks where a hammer is a suitable tool.

Fossiliferous chert pebbles and boulders should never be hit with

a hammer. Same as agate pebbles and silicified wood, they should be cut

with special blades, after inspection from outside and

choosing a

suitable cutting plane. Luckily, stone cutting with

narrow blades is a widespread trade nowadays.

Judging from experience, anyone who has

carried with him or her a hammer for hours feels the urge to hit

something with it, which can mean the destruction of a unique fossil by

irrecoverably shattering it to pieces. Also, most often details are

poorly visible on a fracture face but

better on the naturally smoothed surface. The

safest way to

resist the temptation

to shatter a valuable sample is to leave the hammer at home and take a

pickaxe or big chisel along to poke into the ground or into the gravel

banks.

In order to show that the danger of irreparable damage is real, a

confession of the venerable A.G. Lyon

is

quoted here:

"Preliminary

examination, by removing small chips with a hammer, ... .

Unfortunately, during the preliminary examination, the block shattered,

but two related pieces of moderate size were recovered ..." [3]. Hence,

the title of the related publication reads "On the fragmentary remains

...". In

fact, no chert piece

equalling the shattered one has been found within

half a century, hence the true size and

shape of the fossil have remained obscure.

Incidentally, a fossil closely related to the shattered one serves as

evidence that one can find tiny things by

carefully inspecting the

smooth natural surface of the chert piece:

See photograph and Rhynie

Chert News 29 , 51 , 156.

H.-J.

Weiss 2010

emended

2015, 2018, 2020

[1] N.H. Trewin:

History of research on the

geology and

palaeontology of

the Rhynie area, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh 94 (2004

for 2003), 285-97.

[2] M.

Barthel: Der Madenstein aus dem Rotliegenden des

Windberges.

in: H. Prescher u.a.:

Zeugnisse der

Erdgeschichte Sachsens, Leipzig 1987, S.121.

[3] A.G. Lyon:

On the fragmentary remains of an organism

referable to the nematophytes, ..., Nematoplexus

rhyniensis gen. et sp. nov.

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh

LXV (1961-62), 79-87, 2 plates.