Venation pattern – a distinct feature

of Psaronius tree

fern pinnules

An introductory remark is appropriate here to avoid confusion since

there

are several valid names for different parts of the same fossil plant:

The conspicuous

trunks with their intricate internal structure are known as Psaronius

*.

Their

foliage has got the name Pecopteris

when preserved as a compression fossil but

Scolecopteris

(which literally means “maggot

fern”) when preserved 3-dimensionally with sporangia present.

The ambiguities introduced in this way shall not concern us here.

With increasing amounts of "maggot stones" from Döhlen basin (Lower

Permian)

becoming available since 1993 it has become apparent that some features

of the “maggot fern” vary within wide

bounds: The pinnules may be nearly straight or curved up to

half-circular

shape. Their margins may be nearly smooth or beset with more or less

long and tapering fringes. The number of sporangia fused into a

synangium may

vary from 3 to 6 or rarely 7, and even for a given number of sporangia

per synangium their pattern of arrangement may

differ on one pinnule [1].

It will be difficult to find out to which degree such variability is

due to environmental factors (sun or shade, more or less wet habitat,

salinity of swamp water), age

(juvenile, adult, wilting), etc., and which are inherited features.

Finding out this might give clues concerning the response to a changing

environment, or it might serve as a basis for differentiation between

various strains or species.

There are at least two features which are most likely inherited: (1)

the presence or

absence of forking lateral veins on the pinnules and (2) the angle

between the lateral veins and the pinnule axis. According to Millay

[2], forking veins are absent in Sc.

elegans

and several related species. Scolecopteris

specimens with forking veins

are not rare among those recently

found in Döhlen basin, which is incompatible with the claim in [3,6]

that all recent finds belong to Scolecopteris

elegans.

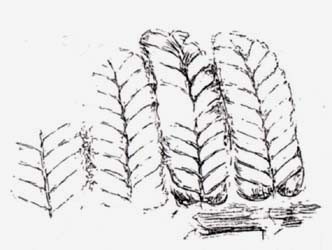

Fig. 1: Pinna of Scolecopteris

with both forking and simple veins on the pinnules.

Width of the picture 6mm.

Although

much more structure information can be preserved in chert compared to

coalified compressions, the vein pattern of the chert specimens is less

conspicuous because the fronds and their parts are usually not lying

flat in the chert but in tilted and distorted positions. Even in the

rare cases where pinnules form a surface relief, the vein pattern is

usually seen less

distinctly than on the often larger frond parts found as

compression fossils. However, there are chert samples with

largely

decayed plant matter where virtually nothing is left but a few forking

veins revealing the presence of fern

foliage.

When trying to measure the angle at which the

veins branch off, one encounters more difficulties: The

pinnule shape implies that the veins are not

curves in a plane but in space, and their curvature tends to vary

shortly after branching off from the midvein. In order to agree upon a

simple procedure of angle measurement, one may choose the tangent to

the vein at a point halfway to the margin, and look at that tangent in

top view, which means project it onto the plane of the pinnule. The

pinnule, however, is usually not plane, hence one has to take the

tangent plane to the pinnule at the position of branching-off for a

reference plane.

This is about the same what one would perhaps intuitively do without

such set

of rules but it may be useful to be aware that other rules would

produce other values of the angle.

Independent

of the details of measurement, a careful look at the veining angles

and other features reveals that the literature

on Scolecopteris

is fraught with a disturbing lot of

inconsistencies waiting to be removed.

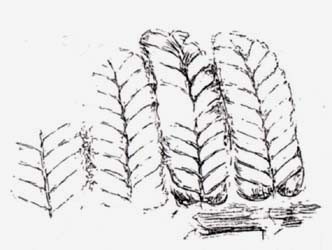

The venations of Fig.2 and Fig.3

differ significantly. By taking the intuitive approach, one finds

angles around 60° in Fig.2 and 45° in Fig.3. Hence, if the angle is

typically 60° for Sc.

elegans as claimed in [3], the pinnules in Fig.2 may be Sc. elegans but

those in Fig.3 are certainly not. (This is also supported by their

length of 7mm since the length of Sc.

elegans

pinnules is 4-5mm [3].) If Fig.3 were Sc. elegans as

claimed in [3], Tafel 2, the 60°-rule would not

be valid.

What is presented as Sc.

elegans

in [4], Tafel VII, and [3], Tafel 5, shows veining angles of 45° and

other features differing strongly from those of the type specimen

(lectotype) in [3], Tafel 1. 45°-venation on alleged Sc.

elegans is also seen in

[5], Fig.6. (There, "Pecopteris

elegans" in the captions of Figs.3,4,6-10 is a mistake.)

The pinna in Fig.1 differs from Sc.

elegans not only by its forking veins but also by angles

smaller than 60°.

When the chert sample with the pinnules pictured in Permian Chert

News 1,

Fig.1, seen on the raw surface in

side view, was recently cut, it

revealed pinnules with 45°-venation

on the cut face, which is not compatible with its assignment

to Sc.

elegans in

[3].

Figs.2,3: Rare examples of Scolecopteris

pinnules distinctly seen as reliefs on the surface of a chert layer.

Height of the pictures 7mm.

Figs.2,3: Rare examples of Scolecopteris

pinnules distinctly seen as reliefs on the surface of a chert layer.

Height of the pictures 7mm.

It requires some experience to reveal a vein pattern like the one

in Fig.1 by

carefully choosing the cut plane of the sample in such a way that as

many pinnules as possible are seen in top view. In this

connection it is worth mentioning that Gert Müller

(Dresden) [7], who found and cut the sample of

Fig.1, was the first one to

find more “maggot stones” after nearly a century of no finds, thus

essentially contributing to the recent upsurge of interest in the

subject.

Finally it appears that distinct features of the vein

pattern,

as forking veins and angles near 45°, provide strong arguments against

the interpretation of all recent finds of Scolecopteris in

Döhlen basin as Sc.

elegans,

as claimed in [3,6]. This is supported by other features,

as the presence or absence of hairs, long or short pedicels

of

synangia,

enclosed or exposed synangia,

and others.

Samples: Old fragments of Lower Permian chert

with more or less rounded

edges, found among younger fluviatile

deposits in Döhlen basin near Dresden, Saxony, Germany.

Fig.1: Found by Gert

Müller

(Dresden) [7] at the type locality of Sc.

elegans near

Kleinnaundorf (1985), photograph

by H. Sahm.

Fig.2: Sample W/3.2, own find (1992), Wilmsdorf,

golf course.

Fig.3: Sample H2/35.2, own find (1993),

Hänichen.

* Uncommonly big and well-preserved specimens

of Psaronius,

the stem of several "maggot fern" species, are on display

at the Naturkunde Museum Chemnitz.

H.-J. Weiss

2011

[1] H.-J.

Weiss: Beobachtungen zur Variabilität

der Synangien des Madenfarns. Veröff. Museum f. Naturkunde Chemnitz

25(2002), 57-62.

[2] M.A. Millay:

Study of paleozoic marattialeans. A monograph of the American species

of Scolecopteris.

Palaeontographica B169(1979), 1-69.

[3]

M.

Barthel, W. Reichel, H.-J. Weiss : "Madensteine" in

Sachsen. Abhandl. Staatl. Mus. Mineral.

Geol. Dresden 41(1995), 117-135.

[4] M.

Barthel : Pecopteris-Arten

E.F. von Schlotheims aus

Typuslokalitäten in der DDR. Schriftenreihe geol. Wiss. Berlin

16(1980), 275-304.

[5] M.

Barthel, H.-J. Weiss: Xeromorphe Baumfarne im Rotliegend

Sachsens. Veröff. Museum f. Naturkunde Chemnitz

20(1997).

[6] M. Barthel:

The maggot

stones from Windberg ridge, Germany.

in: U. Dernbach, W.D.

Tidwell: Secrets

of Petrified Plants. D'ORO Publ. 2002. p65-77.

[7] G. Müller:

private communication.

|

|

2 2 |

2

2

Figs.2,3: Rare examples of Scolecopteris

pinnules distinctly seen as reliefs on the surface of a chert layer.

Height of the pictures 7mm.

Figs.2,3: Rare examples of Scolecopteris

pinnules distinctly seen as reliefs on the surface of a chert layer.

Height of the pictures 7mm.

2

2