Holes gnawed

into early land plants by

elusive creatures

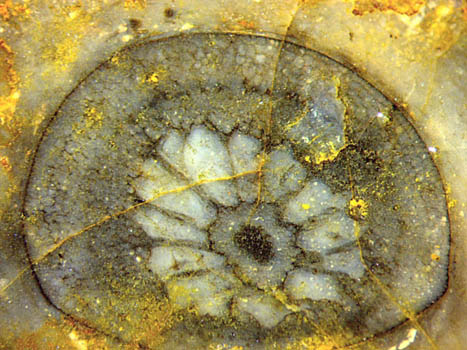

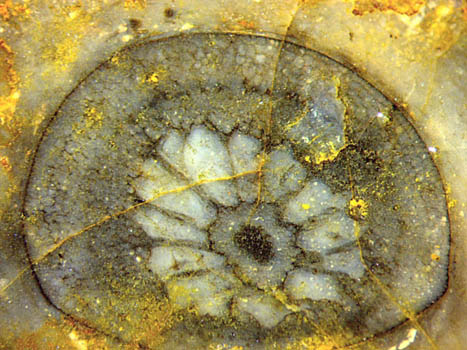

Some of the various phenomena of damage to live

plants are known from the Lower Devonian. A few

specimens of the early land plants as those preserved

in the Rhynie chert show

signs of having been affected by some unknown agent. Most conspicuous

are the big radially oriented void patterns occasionally appearing

on cross-sections of Aglaophyton

(Fig.1). They are certainly not due to creatures but represent a growth anomaly

probably

caused by some unidentified fungus pervading the tissue. Cavities

of quite another type are those left by herbivores, like

the one also seen in Fig.1, above right, and those in Figs.2,3.

Fig.1 (left): Cross-section of Aglaophyton with

"flower-shaped" pattern

of voids due to misguided growth, probably

under the influence of some fungus, and with an additional hole in the

tissue. Image width 4.4mm.

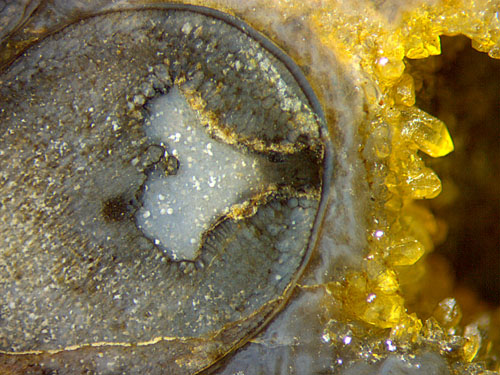

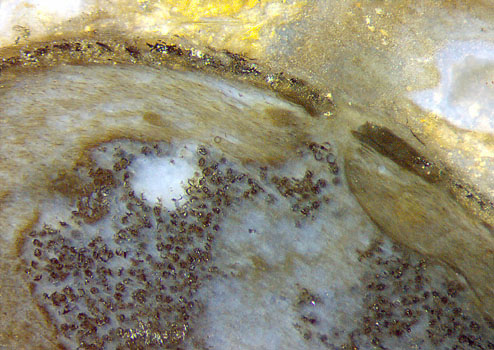

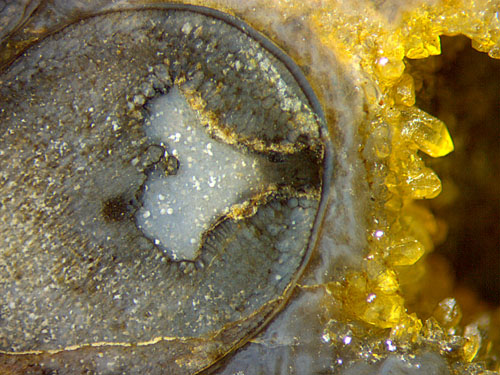

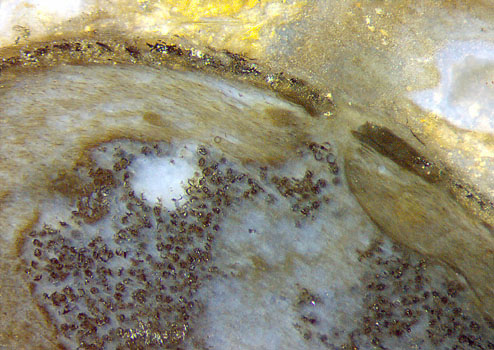

Figs.2,3: Cross-sections

of Aglaophyton

with cavities eaten into the tissue by some unknown creature able to

make an entrance, feed, and retreat.

Image widths Figs.2,3: 4.3mm, 2mm.

By

lucky incidence the cut plane in Figs.2,3 reveals the access hole.

The peculiar shape of the cavity with entrance suggests the idea that a

lengthy creature crept half in, turned to either side while feeding,

then retreated backwards. The creature seems to have visited its

feeding place repeatedly since it could hardly have eaten the amount of

tissue at one time.

Apparently there were creatures demanding food

other than mere parenchyma tissue. They

had gnawed holes into

spore capsules with the intent to get at the spores (Fig.4). Since the

chance of finding a hole on an arbitrary sample face is small, and a

few

have been found on sporangium

walls, they are not quite rare. (The very existence of holes in

sporangia of Aglaophyton

was

doubted not long ago, in 2004.)

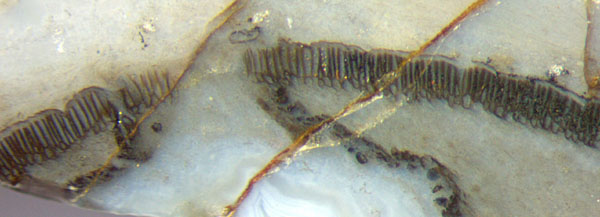

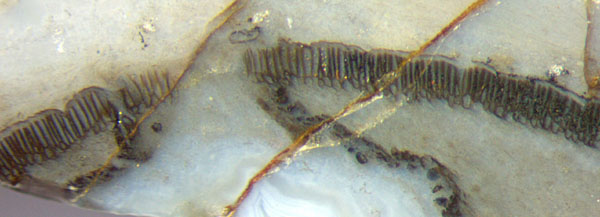

The

outer sporangium wall consisting of the so-called palisade cells,

apparently meant to scare off offenders, had been removed locally to

make the access hole seen in Fig.4.

With another sample, a cavity in the inner sporangium wall

with loose spore tetrads incidentally fallen in is seen in Fig.5. Remains of the

decayed outer wall are

hardly visible at the bottom of the frame.

Fig.4 (left):

Aglaophyton

sporangium with hole gnawed through

the outer and inner wall.

Image width 3.4mm.

Fig.5: Aglaophyton

sporangium detail: cavity

eaten into the inner

wall, scattered spore tetrads.

Image width 2mm.

Fig.6 (below): Aglaophyton

sporangium wall with cavity and access hole in the

"palisade wall".

Image width 3mm.

The damage had been done to the live

plants as can be concluded from repair

activities also seen in similar

cases. This clearly contradicts the statement in [1], p47, that "There

is no evidence of animals that eat living, growing plant material."

What

remains to be done is to find the creatures which made the holes. This

will be difficult since no creature has been seen in these

chert samples. It may be

concluded from Fig.2 and Fig.6 that the diameters of the access holes are about 0.4mm.

There must have been creatures able to

squeeze themselves through these holes.

Other indications of the potential presence of unseen creatures looking for

spores are provided by Nothia

with its big

tubes probably containing poisonous liquid serving as a

repellant, also by Trichopherophyton

with its pointed bristles.

The holes gnawed through unprotected capsule walls and the apparent

precautions against attack on sporangia, like

bristles and poison,

seem not compatible with the statement that "The evidence for

deliberately targeted spore-feeding in the Early Devonian is not

conclusive" [2]. Spherical

or ellipsoidal clots

consisting of spores, possibly taken from sporangia and carefully glued

together, also seem to

support the idea of spore feeding.

To sum up, access holes and cavities had been eaten

into live specimens

of the early land plant Aglaophyton

by elusive herbivores.

Samples:

RhX/1.2 (1.33kg): Fig.1. Rh6/78.2

(0.1kg) found

in 2003: Fig.2. Rh15/84.1 (1.3kg)

obtained from Barron in

2014: Fig.3.

Rh2/75.11 found before 2004: Fig.4.

Rh2/98.1 (9.5kg)

obtained from Shanks

in 2003: Fig.5. Rh6/38.2

(about 0.2kg) found in 2003:

Fig.6. Weights refer

to undivided samples.

H.-J.

Weiss

2021

(slightly modified version)

[1] P.G. Gensel, D. Edwards (eds.): Plants Invade the Land. Chapter 3: W.A. Shear, P.A. Selden: Rustling in the Undergrowth. Columbia Univ. Press (2001).

[2]

K.S. Habgood, H. Hass, H. Kerp:

Evidence for an early terrestrial food web: coprolites from the Early

Devonian Rhynie chert.

Proc.

Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 94 (2004), 371-389.

|

|

180 |