Psaronius /Scolecopteris – a

floating tree fern ?

An idea suggested by fossil evidence

Stems and fronds of Palaeozoic tree ferns of the family Psaroniaceae

[1] have got separate names for practical reasons: Usually they are

not found together so that it is virtually impossible to establish a

species covering both foliage and stem. Or else there can be several

species present in the same petrified biotope, which likewise makes it

difficult to find out which foliage belongs to which stem. The stems

are called Psaronius,

the foliage is called Pecopteris

if preserved as a compression fossil, otherwise it is subdivided into

several genera including Scolecopteris.

Nowadays

the name Psaronius

is also used for the whole plant but the other names are still

valid. The genus Scolecopteris

has been subdivided by Millay

[1] into 26 species.

A drawing

by J. Morgan [2] thought

to be more or less representative for some or all

Psaronius

/Scolecopteris

species has been published

repeatedly in monographs [3,4]. These drawings, however, begin always

above ground level although there are reasons to assume that a good

deal of the tree is hidden below.

Any attempt to reconstruct the lowest part of Psaronius has to

start

from the peculiar structure of the tree trunk: Most of it consists of

apparently strong aerial

roots running down the stem, connected by soft

tissue. The stem proper, without the roots, is widest at the top where

it bears the fronds but very narrow near the ground. It is as narrow

there as it had been in the juvenile stage because there is no

subsequent lateral growth. There is no primary root left, hence the

whole tree rests on its aerial roots.

Far-reaching conclusions can be drawn from one feature of the aerial

roots: As they get near the ground while growing downward, they develop

air-filled tissue, the aerenchyma, thereby largely increasing their

cross-section. They become more and more detached from each other,

hence their lower parts are called free aerial roots.

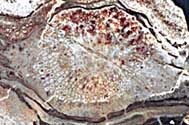

The free aerial roots are seen beautifully preserved on cross-sections

of

the

lower part of the large Psaronius

tree trunks displayed in museums [5] but

usually they are not found fossilized in the

ground.

This may be due to the event which supposedly led to the fossilisation

of the conspicuous trunks: a volcanic eruption causing a

pyroclastic flow moving down the slopes at high speed (typically about

400km/h) and spreading over level ground, thereby tearing the trees

from their

base and possibly blowing away their habitat as well, scattering the

roots

together with the soft ground or mud. So it can be understood that the big Psaronius specimens displayed at the Naturkunde Museum Chemnitz had not been found silicified together with the related parts of the tree.

Luckily, the fossilisation of tree ferns was not always

preceded by

catastrophic events so that occasionally all parts of the tree, namely

the free aerial roots in the ground, the stems with the fused aerial

roots, and the foliage, are found in the swamp matter turned into chert.

Numerous chert samples representing a wet habitat with layers of peat

and mud silicified while at or near the surface have been found lately

in the Lower Permian Döhlen basin. Moults of the aquatic crustacean

Uronectes

and extended microbial layers found among the remains of Psaronius /

Scolecopteris indicate

that

there was not only wet ground but free water as well. Part of the chert

samples contain aerial roots (Figs.1,2), some of which are preserved in

a non-collapsed state.

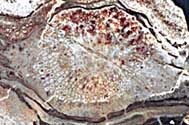

Fig.1: Psaronius "free"

aerial roots

in the ground, more or less squeezed before silicification, aerenchyma

(air-filled tissue) poorly visible here, layered peat consisting

of collapsed roots below. Döhlen basin (Lower Permian), type locality of

Scolecopteris. Width of the picture 9cm.

Fig.2 (right): Psaronius

free aerial root cross-section with aerenchyma,

originally air-filled tunnels up to 0.5mm across.

Width 1.5cm.

Site: Type locality of the "Maggot fern" Scolecopteris elegans at the boundary between Kleinnaundorf and Burgk, Döhlen basin, Saxony, Germany.

Samples:

Fig.1: Bu13/31.3 ; Fig.2: Bu13/35.2 ; found in 1998 on the property

Kohlenstr. 8. The recovery of these and numerous other samples has

been furthered by the interest of the owners, family Beyreuther.

The idea suggests itself that the mass of tangled and branching

air-filled free aerial roots would have enough buoyancy in soft mineral

mud or even in water or organic mud to support the whole tree. This

would be doubtless an advantage or even a precondition for

the growth of trees on

wobbly ground. Since Nature usually realizes favourable options, it is

worth while considering the implications of such design. One

implication is evident from Fig.3.

Fig.3: Advantage of a floating tree in strong winds: Does not get

rooted up or broken off.

If

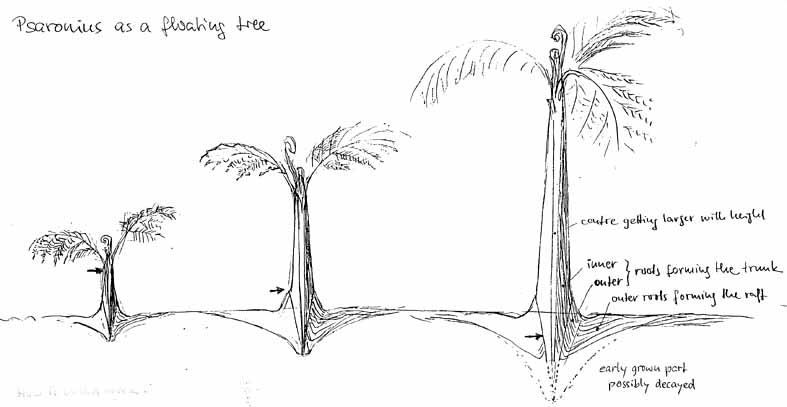

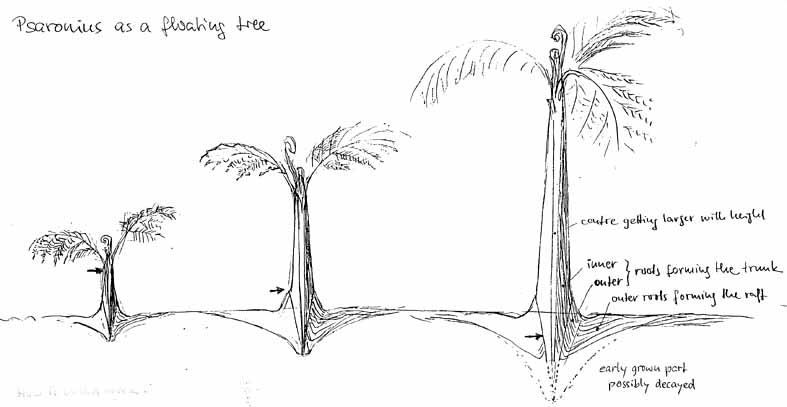

there were floating trees among the several Psaronius species,

what

could be predicted about their successive growth ? The answer is

visualized in Fig.4.

The tree sinks in as it grows, with buoyancy

increasing such that it keeps equilibrium with the increasing weight.

This may explain why the lowermost part of the stem with its tiny

centre dating back to the earliest growth stadium is never seen on the

conspicuous polished stem cross-sections displayed in museums [5]: This

oldest part of the plant had most probably been dead and gone before

the tree became big.

Fig.4: Hypothetical design of floating Psaronius:

Equilibrium

of the growing tree is maintained by successively sinking in, as

indicated by the arrow supposed to be fixed to the trunk.

Stability against upsetting is brought about by the large raft of

air-filled roots.

H.-J.

Weiss

2011

[1] M.A. Millay:

A review of permineralized Euramerican Carboniferous tree

ferns. Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn. 95(1997), 191-209.

[2] J.

Morgan: The morphology and anatomy of American

species of the genus Psaronius. Illinois Biol. Monogr. 27(1959), p1-108.

[3] W.N. Stewart,

G.W. Rothwell: Paleobotany and the

Evolution of Plants. Cambridge Univ. Press 1993, p228.

[4] T.N.

Taylor, E.L. Taylor, M. Krings: Paleobotany,

Elsevier 2009, p418.

[5] R.

Rössler: Der versteinerte Wald von Chemnitz. Museum für

Naturkunde Chemnitz, 2001.

|

|

7 7 |

7

7

7

7