Beautiful Permian wood from Döhlen

Basin

Wood from Permian conifers, summarily named Dadoxylon for

simplicity, is usually less interesting to fossil collectors since

most often it

does not show distinct features like the central pith or wide pith

rays. Despite of the usually dull aspect, the

interest may be aroused by secondary phenomena related to degradation

and silicification, which may result in beautiful pictures.

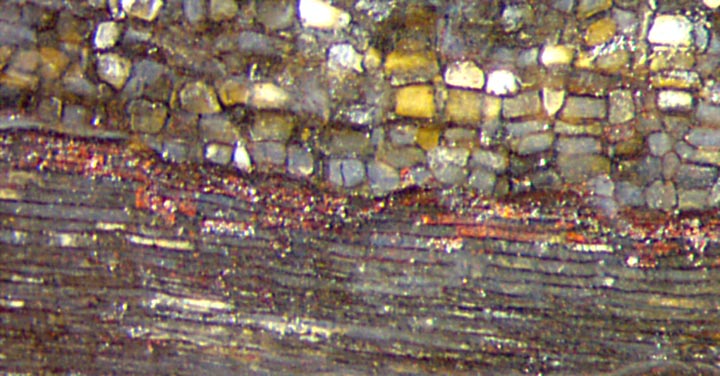

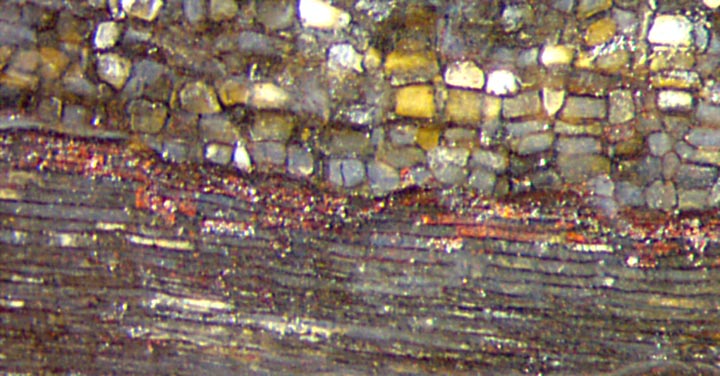

Fig.2: Wood

cut lengthwise with central pith above. [ 1 ]

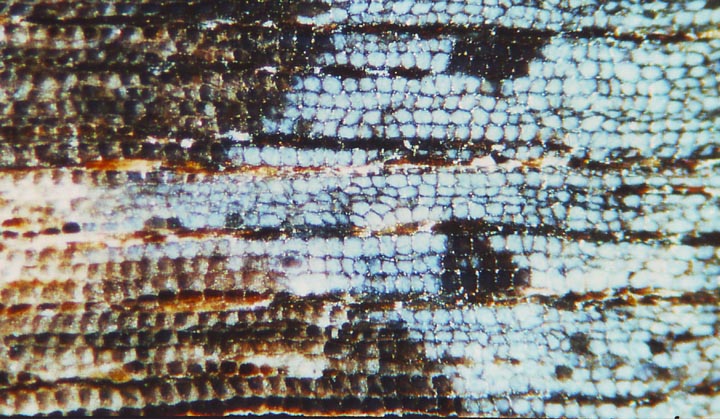

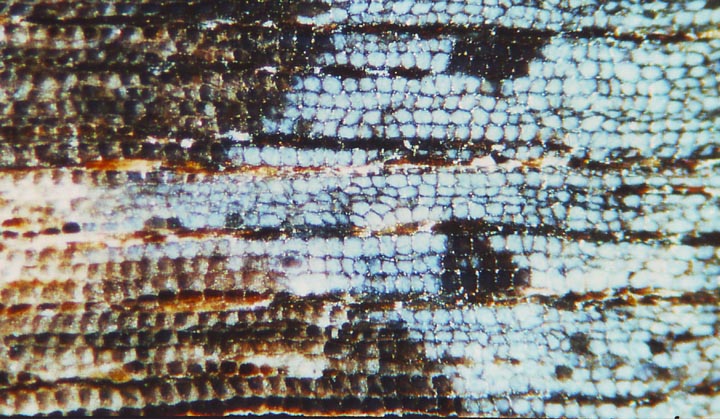

Fig.1: Cross-section, cells with chalzedony fills: bluish white, black, or clear with shadows in the depth

(left). Figs.1,2: same scale, widths

2mm.

The aspect of the chalzedony seems to

be very sensitve to tiny differences in the chemical composition of the

compartment. Hence, the fill of neighbouring cells may be clear, white,

or black as in Fig.1 or variously coloured as in Fig.2.

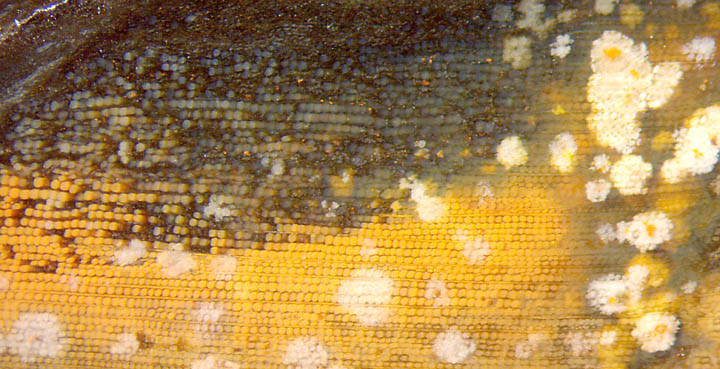

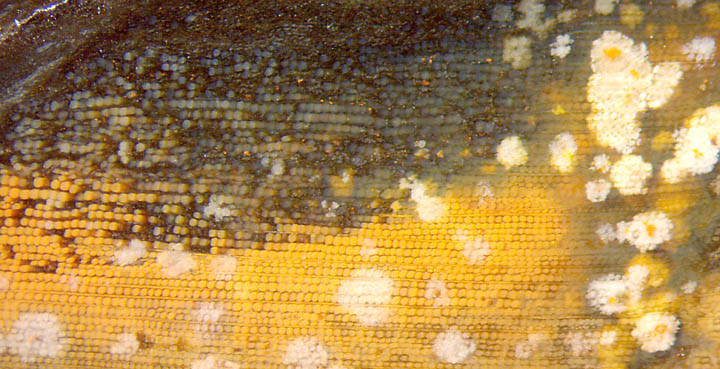

Fig.4: Cells with yellow stained chalzedony,

recrystallized as white spots

with rare "daisy aspect". Picture width 5mm.

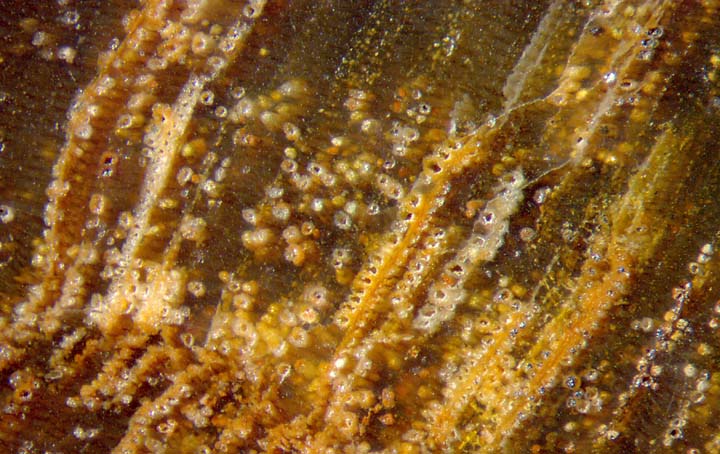

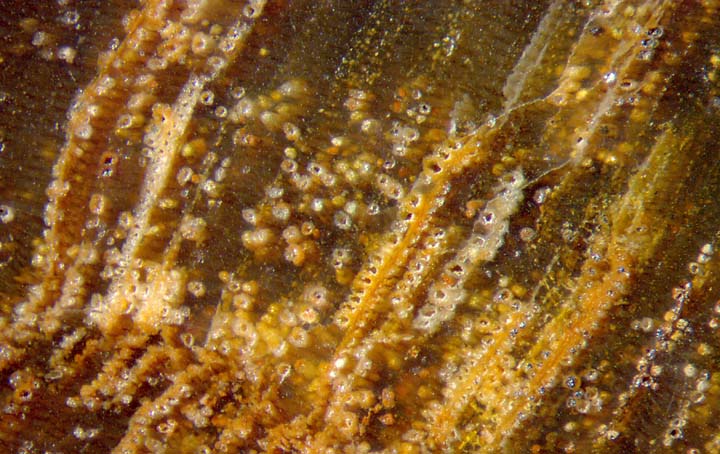

Fig.3: Wood

well silicified except for the hole in every cell: unexplained

rare phenomenon. Picture width 4mm.

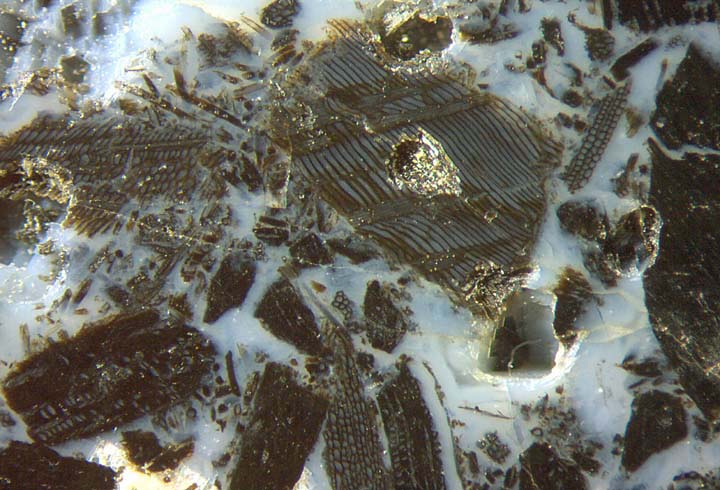

Fig.6: Wood

disintegrated while soft, then silicified: no charcoal.

Width 5mm.

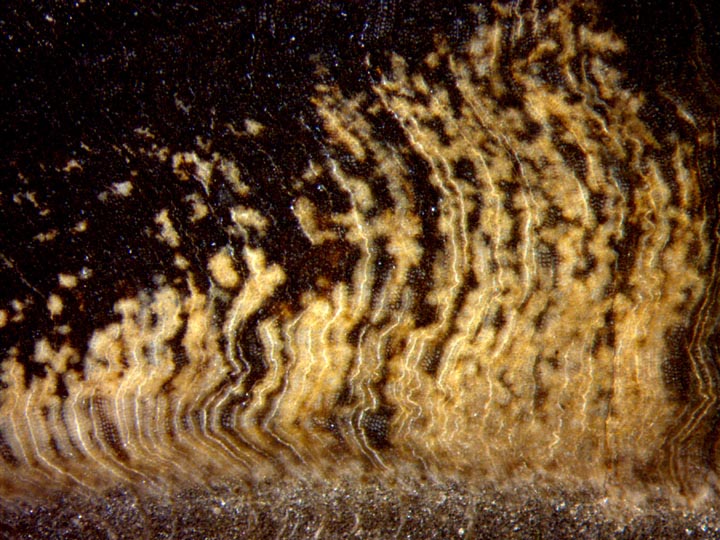

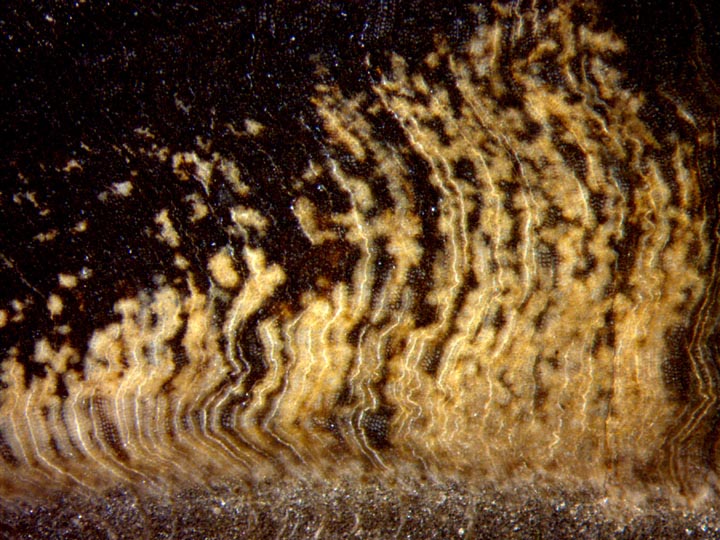

Fig.5: Wood with small cells,

deformed, partially bleached. Width 5.5mm.

Arguably,

Fig.5 may be considered the most beautiful of these pictures. The

flame-like aspect is due to bleaching along the radial wood rays and to

slight radial compression which caused the rays to kink irregularly.

The bleaching by carbon oxidation was possibly caused by oxygen diffusion along the rays. This wood

differs from the others by narrower cells, hard to see here as tiny

dots in

some places, better seen with the same sample in [ 2 ].

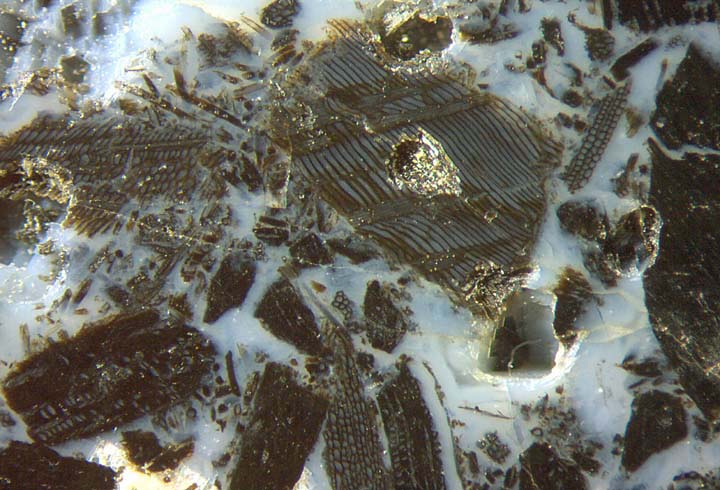

Finally, Fig.6 may be

considered the most controversial of these pictures. This sample from the Wilmsdorf golf course has provided essential arguments so that prominent palaeobotanists (M. Barthel, Berlin, and R. Roessler,

Chemnitz) had to admit that they

were wrong with their favourite interpretation of black Permian wood as

fossil charcoal [3-5]. Looking carefully reveals that the wood was soft

while disintegrating:

See [ 6 , 7 ].

Additional evidence contradicting the charcoal

interpretation is offered by the smallest parts in Fig.6. Crushed

charcoal would never yield tube-like fragments representing

individual cells. These details indicate that the tissue had lost its

coherence, apparently by prolonged submersion, so that the wood could

easily disintgrate, producing fragments of any size and shape, among

them separate cells.

Unrelated to the above problem but worth mentioning are several

cavities in the polished face of Fig.6. They are due to dissolved calcite

crystals which had grown in the wood or in plain chalzedony. One not

yet dissolved white calcite crystal is seen below.

Samples: from Döhlen Basin near Dresden, Saxony; kept in

the own collection.

Fig.1: Kc/14.1, found by

Andrea

Weiss at Kleincarsdorf in 1997;

Figs.2-6: W/42.1, W/48.1,

W/95.1,

W/35.1,

W/55.3,

found

during the preparation of the golf area at Wilmsdorf in the

early 90s;

H.-J.

Weiss 2019

[1] www.chertnews.de, Fossil

Wood News 31

[2] www.chertnews.de, Fossil

Wood News 33

[3]

R.

Noll, D. Uhl, S. Lausberg : Brandstrukturen an

Kieselhölzern der Donnersberg Formation.

Veröff. Mus. Naturkunde Chemnitz 26

(2003), 63-72.

[4] R.

Rössler : Der versteinerte Wald von Chemnitz. Museum f.

Naturkunde Chemnitz, 2001, 179.

[5] R.

Noll, V. Wilde : Conifers from the „Uplands“ –

Petrified wood from Central Germany,

in: U. Dernbach, W.D. Tidwell :

Secrets of Petrified Plants, D'ORO Publ., 2002, 88-103

[6] www.chertnews.de, Fossil

Wood News 9

[7] www.chertnews.de, Fossil

Wood News 35

|

|

34 34 |

34

34

34

34