Cracks

Crack initiation and propagation is a highly complex and interesting

phenomenon. Part of it will be considered in more detail later.

Meanwhile a few facts about cracks are stated here, including more or

less trivial ones.

Crack initiation and propagation is a highly complex and interesting

phenomenon. Part of it will be considered in more detail later.

Meanwhile a few facts about cracks are stated here, including more or

less trivial ones.

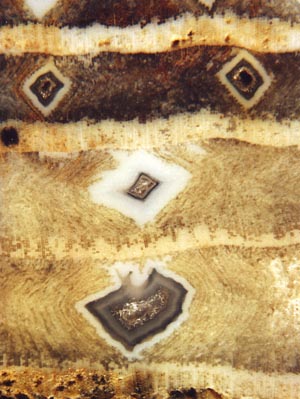

Fig.1: Silicified peat consisting of squeezed Psaronius with

narrow

cracks apparently defying any reasonable explanation.

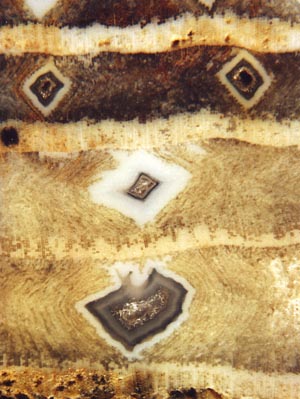

Fig.2: Fossil wood with

wide tunnel-like cracks whose formation can be

essentially understood as brought about by some

combination of shrinkage, mechanical anisotropy, silica deposition, and

deformation under

vertical compression. (See Funny

Faces.)

Cracks

may appear if the

tensile stress exceeds the mechanical strength of a material. (Some

materials do not fail by fracture but by flow.)

Cracks

may appear if the

tensile stress exceeds the mechanical strength of a material. (Some

materials do not fail by fracture but by flow.)

Stress

may be transient as in impact or permanent as under applied load.

Shrinkage gives rise to tensile stress if

restricted by constraints.

The question whether stress is the cause of

strain or vice versa is meaningless.

In case of variable strength, the

crack chooses an easy path.

Although most of the cracks seen on cut chert faces will probably

never be really understood, trying to draw information from cracks may

be worth the effort.

The decay-resistant cuticles on the surface of land plants

make discontinuities in the chert which are faces of low strength,

which means easy crack paths.

Therefore, the crack running along the spherical surface of Pachytheca

indicates that this "enigmatic organism" was covered by a cuticle and

thus adapted to sub-aerial conditions.

Most

of the cracks seen in cherts had been healed soon after their formation

by deposition of silica in the gap, possibly from the same source which

provided silica for chert formation. Cracks

which did not

heal may have led to the disintegration of the chert layer into

rectangular or polygonal fragments found now among the gravel of

ancient and recent streams.

Narrow cracks with hardly visible gap had formed most

probably in hard and brittle material. Very wide shrinkage

cracks as

they are occasionally seen in petrified peat

and petrified wood

must have formed in an early stage of silicification when the silica

gel was still so weak that it did not preclude further shrinkage but

was able

to keep the fragments suspended in their original position.

There

are cases where cracks can help to reconstruct the sequence of events

which led to the final aspect of the sample. A wide crack through a

white spot

in petrified wood proves that the spot had formed at an early stage

when all was still

soft, contrary to another hypothesis.

Cracks which are narrow in the depth but

widen into a V-shape

on the surface as in the image on the right are secondary formations

resulting from spalling fracture due to repeated impact of pebbles and

boulders on the edges. They have been mistaken for damage by insects.

Cracks due to interface debonding can bring forth unexpected

shapes.

The danger of misinterpretation

of cracks as cell walls

of fossil plants is there, especially with fossil polygonal

crack patterns.

Crazy cracks which seem to defy any explanation are seen here : Fossil Wood News 39.

H.-J.

Weiss

2012

updated

2014, 2021

Cracks

may appear if the

tensile stress exceeds the mechanical strength of a material. (Some

materials do not fail by fracture but by flow.)

Cracks

may appear if the

tensile stress exceeds the mechanical strength of a material. (Some

materials do not fail by fracture but by flow.)