Ventarura

- peculiar and confusing

Every one of the seven early land plants hitherto discovered in the

Lower Devonian chert from

Rhynie, Scotland, is characterized by at least one unique feature.

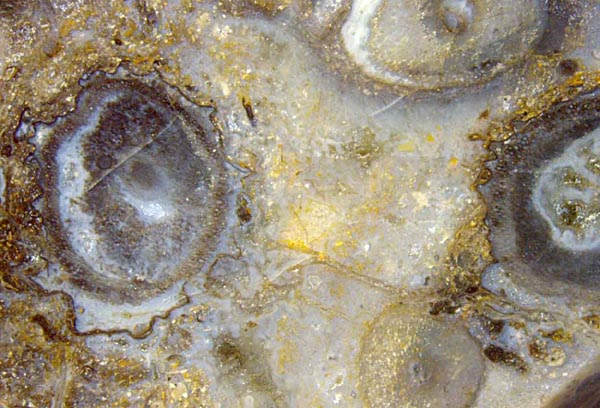

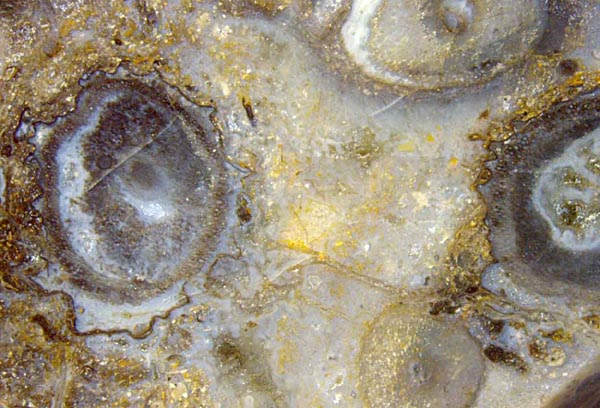

Plant cross-sections with a dark concentric ring at some distance from

the periphery and consisting of rot-resistant cell walls are

characteristic of the lately discovered Ventarura

[1].

The ring seen on cross-sections is, of course, a tube inside the stem.

Unfortunately, reality is not as simple as this: The characteristic

feature may be a ring segment instead of a closed ring, it may be pale

instead of dark, and it may be so close to the periphery that the whole

can be mistaken for a hollow straw of the most abundant

plant in the

Rhynie chert, Aglaophyton.

Resulting from a peculiar growth mode, the originally circular ring may

have been compressed into a crescent shape while the stem cross-section

remained circular. As an exceptional phenomenon, there can be two

concentric rings. Also

it must be kept in mind that the the ring or tube is there in the upper

parts of the plant only, which means that the lower parts of Ventarura are not

readily recognized as such.

A few of the facts and difficulties mentioned here can be illustrated

by means of Fig.1 with 4 cross-sections of starkly differing aspect.

Fig.1

(far left): Ventarura with

and without dark rings on cross-sections.

Fig.1

(far left): Ventarura with

and without dark rings on cross-sections.

Width of

the picture 13.5mm.

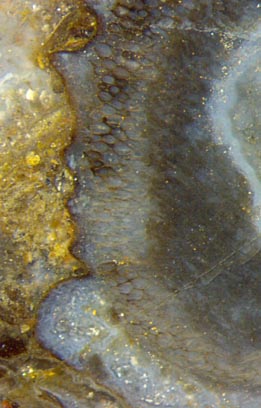

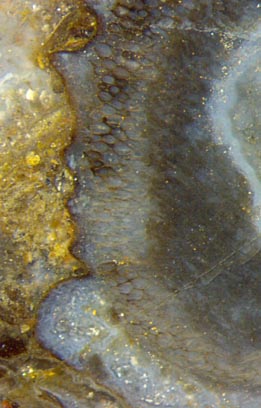

Fig.2: Degraded Ventarura, detail

of cross-section on the right of Fig.1, (left to right):

ruggedly shrunk and decayed outer cortex with a layer on the cuticle

partially stained black,

ring-shaped fraction of well-preserved cortex with cell walls partially

stained black, degraded inner cortex, cavity lined with

bluish chalzedony.

The

often conspicuous dark rings (or tubes in 3D) had been interpreted as

sclerenchymatic tissue [1] but

recently re-interpreted as a manifestation of an unexplained

persistence

of some fraction of

middle cortex [2].

(We

apply the terminology used in [1]: The tissue between the central

strand and the epidermis is thought to be subdivided into inner,

middle, and outer cortex.)

Although the aspect of the typical closed ring in the

section on the left in Fig.1 is spoiled by a large dark inner

cortex area

of no relevance concerning the structure of the plant, the

combination of dark ring and rugged outer boundary is strong

evidence of Ventarura.

By queer

coincidence there is a conspicuous dark ring in the section on the

right. It is confusing since it might be

misinterpreted as evidence of Ventarura if

looked at superficially. A closer look reveals that it is only dark

inner cortex, likewise irrelevant as the dark area on the left of this

image. There is evidence of Ventarura,

though less conspicuous: The relevant ring is seen between the

irrelevant

dark

inner cortex fraction and the shrunken outer cortex. This ring

is partially dark or pale, as seen more clearly on the enlarged

detail in Fig.2. Obviously the dark aspect of part of the ring is not

brought about by thick-walled sclerenchyma cells but by some black

deposit, probably of microbial origin, on the

thin walls of rot-resistant cortex cells arranged as a

ring. It has been shown

that the

black deposit had been only loosely connected to the cell wall and may

have flaked

off before silicification [2]. The deposit is probably of the

same type as often

present on the cuticle, where

it may cause the cuticle to peel off and form a curl [2].

No

explanation is proposed here concerning the origin and purpose of the

persistent tissue shaped as a (partial) ring or tube. More questions

arise from a peculiar growth mode whereby the ring or tube became

deformed into a crescent shape (Figs.3,4).

Figs.3,4: Cross-sections of Ventarura shoots

with persistent rings squeezed into crescent shapes by another

shoot grown inside later.

Apparently

a new shoot had grown inside the old one along the outer cortex,

thereby pushing the old tissue aside so evenly that a new circular

outline was formed. The old inner cortex was probably degrading by that

time, offering virtually no resistance. Thus the persistent ring became

crescent-shaped, which implies large deformation during the re-shaping

process. This means that the ring must have been soft, which is another

piece of evidence contradicting the sclerenchyma hypothesis.

The growth of a new shoot inside the old one is

more advanced in Fig.4 compared to Fig.3. The process can go

so far that the old shoot degrades into

a mere sheath around the new one.

The formation of new shoots in old ones is not rare with the two

zosterophylls

Ventarura

and Trichopherophyton.

It

is not known in which way this process begins. It may also begin in the

inner cortex so that the persistent ring, if there is any, remains

circular as in Fig.5.

Fig.5: Cross-section of Ventarura

with a small new

shoot inside the persistent ring. Width of the

picture 5.4mm.

Among the cross-sections shown here, Fig.5 is the least confusing one.

With the rugged outline resulting from shrunken and partially vanished

outer

cortex and the well preserved mid-cortex ring, the typical

features of Ventarura

are there.

The

outline is marked by a black deposit on the cuticle. Similar as in

Fig.1, the ring is partially dark or pale. Silicification has preserved

the central strand of irregular shape, a new shoot with own central

strand and circular

cross-section, and some remains of the degraded inner cortex.

Again it is not known where the new shoot came from and where it would

end.

It

has been proposed that new shoots seen inside old ones had grown along

dead plant parts [3] but there are several pieces of contrary evidence.

Hence it remains undecided how to interpret composite plant structures

like those in Figs.3-5 and in Rhynie

Chert News 16.

H.-J. Weiss

2015

[1] C.L.

Powell, D. Edwards, N.H. Trewin:

A new vascular plant from the

Lower Devonian Windyfield chert, Rhynie, NE Scotland.

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, Earth Sci.

90(2000 for 1999), 331-349.

[2] H.-J. Weiss:

Rhynie chert - Implications of new finds. EPPC 2014, Padua.

[3] D.

Edwards : Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and

Windyfield cherts.

Trans. Roy. Soc.

Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 94(2004 for 2003), 397-410.

|

|

82 |

Fig.1

(far left): Ventarura with

and without dark rings on cross-sections.

Fig.1

(far left): Ventarura with

and without dark rings on cross-sections.