Enigmatic black deposit in Rhynie chert

There are dark or black deposits of various

type in the Rhynie chert: at the bottom of once water-filled pockets

present

during silicification, as level plates in such pockets or within Horneophyton

tubers, on detached

or adhering plant cuticles, or on cell walls of

early land plants. In the case of Ventarura,

cells with

dark deposit on the walls have been interpreted as sclerenchyma, which

is most probably erroneous [1]. The black deposit shown here is of a

different aspect. It looks as if once it had been an oily substance

within a narrow gap of a crack, then had become solidified and

glossy.

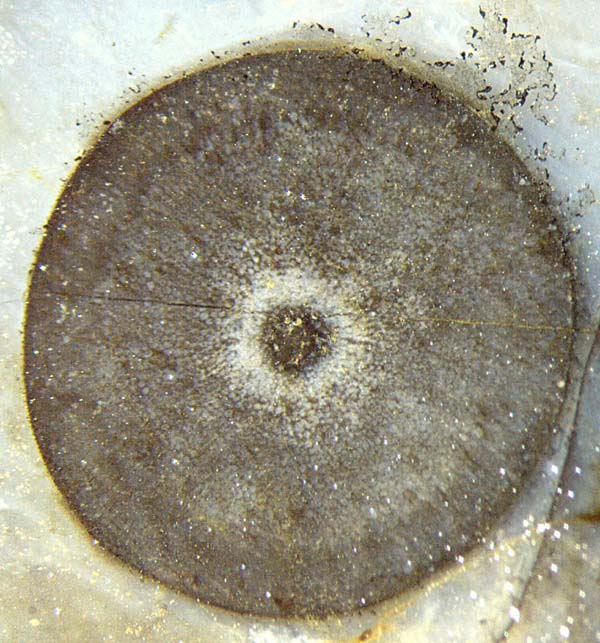

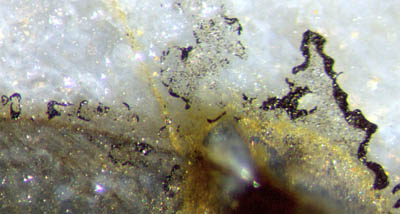

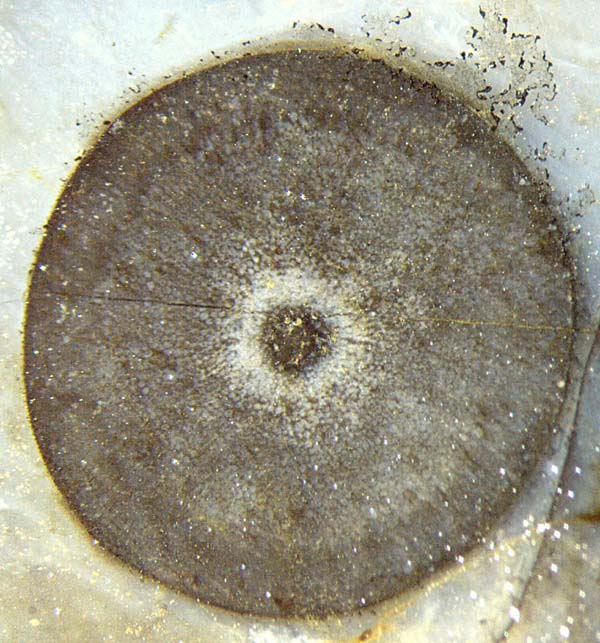

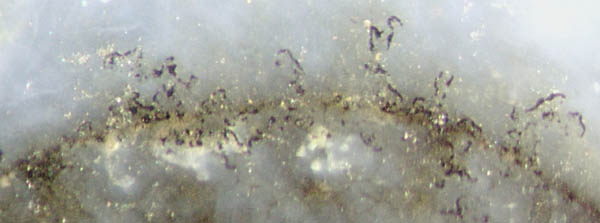

Figs.1-3: Aglaophyton

cross-section, 4 mm, with dotted areas along the

circumference, partially bounded by glossy black blobs

of various shape; image successively enlarged.

Figs.1-3: Aglaophyton

cross-section, 4 mm, with dotted areas along the

circumference, partially bounded by glossy black blobs

of various shape; image successively enlarged.

As seen on the Rhynie chert fragment in

Figs.1-5, glossy black blobs are irregularly arranged near the

well-preserved cross-sections of Aglaophyton.

Remarkably, the blobs are seen ...

(1) only on the matt upper fracture face of the

chert

layer fragment,

(2) nearly always on the very face but not inside

the chert,

(3) always at or not far from either side of the

plant contour,

(4) bounding dotted areas.

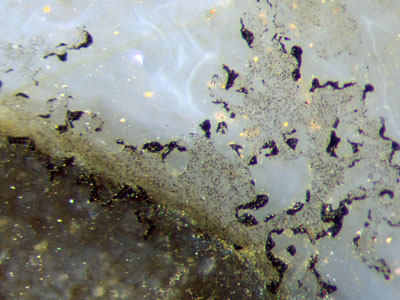

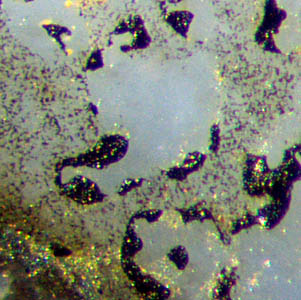

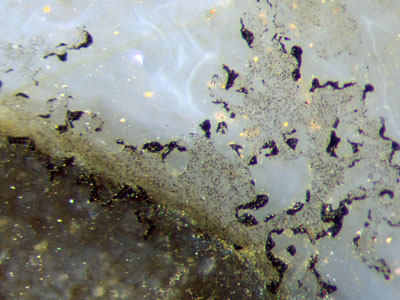

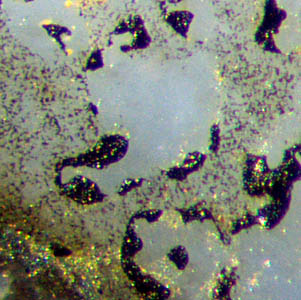

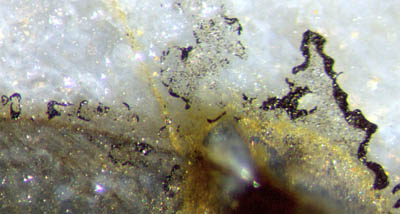

More glossy black matter of this type is shown in Figs.4,5.

Figs.4,5: Black substance

near the contour of Aglaophyton

sections

on an old chert fracture face. Width of either picture 1.4mm.

Figs.4,5: Black substance

near the contour of Aglaophyton

sections

on an old chert fracture face. Width of either picture 1.4mm.

Obviously the black substance in Figs.1-5 had been

deposited after a horizontal crack had run along the chert layer. This

could have happened at any time within 400 million years, quite recent

times included. Unfortunately, the observations discussed here seem to

provide only little information suitable for narrowing this huge time

span.

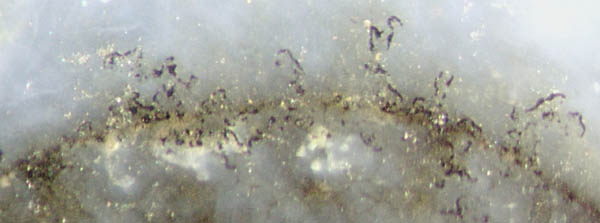

Fig.7. Flat blobs of black substance on a face

inclined to the picture plane. Width of the picture 2mm.

It

takes some effort to imagine the 3D-situation related to Fig.7. Let the

bluish area on the right be called the main fracture face of the

sample. The brown area on the left is the cylindrical replica of an

epidermis seen from within.

Here the crack had left the main

fracture face when it came upon the cuticle as an easy crack path.

The

string of black patches marks the intersection of the cylindrical face

with the imaginary continuation of the main

fracture face.

The patches are inside the chert behind the brown cylindrical face but

are out in the open on the bluish flat face. All of them are on the

common flat face, (which is not perfectly plane across the sample).

Fig.7 suggests that ...

- the main

fracture face once

had been one real crack with a narrow gap,

- black substance or its precurser

moved from the plant into the gap and arranged itself in peculiar ways,

- subsequently the crack more or less healed,

- later the chert layer broke into pieces, also

along the old "main fracture face",

- thereby the black substance was laid bare at the

surface, except for rare deviations as in Fig.7.

Apparently all

this could not have occurred quite recently but this does not mean that

it must have occurred in the distant past. (In this connection, one

should be careful not to confuse the black deposit of the rare glossy

type

considered here with the abundant black crusts, often circular ones,

recently formed on any stones, probably by cyanobacteria.)

Obviously the black substance or its precurser must have been in a

(transient) mobile or

fluid state. From the above observation (3) it may be concluded that

the

source of the possibly oily substance had been at the surface of the

embedded plants, which poses another problem

and suggests a solution. Usually the plants do

not

emit organic substances while or after being silicified. Something

unusual must have been going on. One thinkable

option is the following.

It

is known that the cuticle covering the epidermis is highly

decay-resistent so that it can persist in the chert over geological

timescales (and may make its presence felt as an easy crack

path as in Fig.7). It

consists of polymers and waxes which do not move about in the

chert. Perhaps the solid cuticle or some of its components can be

turned into mobile

or

fluid decay products by the action of microbes. In the present case,

the microbes could have reached the embedded plant through the gap of

the crack and broke down cuticle matter into fluid decay products

seeping out into the gap. Apparently a transient liquid substance is

seen in the

above pictures, with scattered dots of irregular

shape, which could be clusters of microbes. The comparatively big blobs

seem to have formed by accumulating some amount

of liquid of oil-like consistence, dots included, and by subsequent

transformation into a glossy black

solid substance.

It

must be admitted that this is not really an explanation since some

questions concerning the process steps have remained open.

If further investigations confirm the interpretation of these pictures

as evidence for the mobilisation of cuticle substance, they could serve

as illustrative material for the formation of mineral oil from plant

matter.

Photographs: Taken from the raw surface of a Rhynie

chert fragment found by Sieglinde

Weiss in 2014.

H.-J.

Weiss

2014

[1] H.-J.

Weiss :

Rhynie chert – Implications of new finds. European

Palaeobotany and Palynology Conference 2014, Padua.

|

|

70 |

Figs.1-3: Aglaophyton

cross-section, 4 mm, with dotted areas along the

circumference, partially bounded by glossy black blobs

of various shape; image successively enlarged.

Figs.1-3: Aglaophyton

cross-section, 4 mm, with dotted areas along the

circumference, partially bounded by glossy black blobs

of various shape; image successively enlarged.

Figs.4,5: Black substance

near the contour of Aglaophyton

sections

on an old chert fracture face. Width of either picture 1.4mm.

Figs.4,5: Black substance

near the contour of Aglaophyton

sections

on an old chert fracture face. Width of either picture 1.4mm.