Cell-size clots in bennettitalean

tissue:

No oribatid mite coprolites

It is surprising to see how some dubious ideas

persist once they have

entered into the scientific literature. One notorious

example from palaeobotany concerns small dark clots in fossil plant

tissue for which a plausible explanation had to be found. As the clots

were usually seen in damaged parts of the tissue, the idea suggested

itself that they were droppings of some small creature feeding on the

tissue. This idea, believable as it

seemed, was fraught with more than one

problem: First, no fossil creature was seen near and far. This was

taken as an

excuse for introducing guesswork. Since mites are known to feed on

plant

matter, the mite coprolite idea was brought up. The guesswork became

even more specific: The mites, although elusive, were specified as

oribatid mites, and "oribatid mite coprolites"

became a popular term in the palaeobotany

literature since the 1990s. Those palaeobotanists

who readily adopted it had apparently not noticed an observational

fact: Where there are dark angular clots in damaged tissue, one can be

sure that their size and shape variation is compatible with the size

and shape variation of the cells of nearby intact tissue, which poses

another problem.

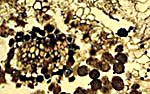

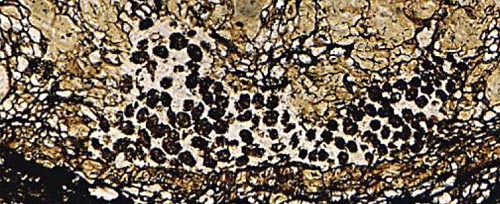

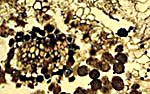

Figs.1,2:

Cell-size clots in damaged tissue of triassic

bennettitalean roots, details of Figs.6G,D in [1], interpreted

as oribatid mite coprolites there. Note the clot sizes fitting to the

largely differing cell sizes. In Fig.2 there are small cells filled

with clot matter in a coherent row, and larger loose clots on the right. Width

of the pictures 0.3mm (provided that the scale bars in [1] are correct).

It is hard to believe that it did not occur to those dealing with the

subject that such coincidence is strong evidence against the coprolite

interpretation. Perhaps it did occur later to those authors who

preferred not to propagate that interpretation any more. However, none

of them has expressly retracted the coprolite hypothesis. Therefore it

is necessary to comment on every such publication, which has been done

in the sequence as they have become known to the present writer. (See

Google: oribatid mite coprolites, or "Wood rot or

coprolites" on this website.)

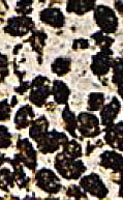

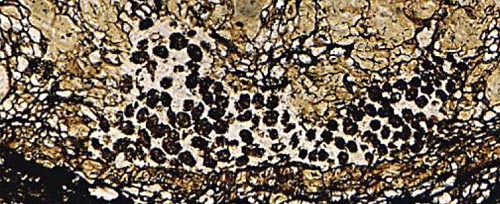

Fig.3: Cell-size clots in partially decayed tissue of a cretaceous

bennettitalean stem, detail of Fig.4E in [2], interpreted

as oribatid

mite coprolites there.

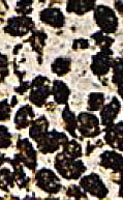

Fig.4 (right): Detail of Fig.3, polygonal outlines of angular clots

called

"spherical to ovoid" in [2].

The arguments concerning the misinterpretation of the clots are the

same as given repeatedly before. In case of good preservation, for

virtually every one of the loose clots an intact cell of fitting size

and shape can be found in the tissue, which strongly suggests the

conclusion that the clots had been some kind of cell casts which came

tumbling out when the cell walls broke down. Clot formation inside

cells and breakdown of the walls is most probably due to the same

cause. Fungi have been observed to form dense tangles of very thin

hyphae inside cells, and it is known that they are able to break down

cell walls of plants [3].

The clots in Figs.3,4 are described in [2] as "spherical to ovoid" with

"smooth

to slightly bumpy" surface but it is easily seen that the alleged bumpy

spheres are rather angular, often with polygonal outline, and even

right and acute angles are seen, as expected from replicas of the cell

lumen. This applies also to Fig.5.

The polyhedral clots usually misinterpreted as coprolites may be the

only fossil evidence for the original cell sizes and shapes of

vanished

or compressed tissues. The empty cells have retained their

shape in Figs.1,2 but part of them have become deformed or collapsed in

Figs.3,5.

Damaged plant tissue with the same aspect as in these images is usually

called

a frass gallery although there are no specific features of the damage

which would justify such interpretation. There are alleged galleries so

narrow that no herbivore could have crept there. There are alleged

coprolites in intact cells where no herbivore could have

deposited them.

Fig.5: Angular clots in a partially damaged triassic

bennettitalean root, detail of Fig.6O in [1],

interpreted as oribatid

mite coprolites there.

Finally it can be concluded that the above evidence does not support

the hypothesis of oribatid mite activity in cretaceous and triassic

bennettitaleans. It remains to be checked whether or not other

reports on herbivore coprolites in bennettitalean fossils stand

a critical revision or have to be re-interpreted as wood rot as it has

been done with numerous cases of alleged oribatid mite coprolite

sightings in plant tissue.

H.-J.

Weiss 2013

[1] C.

Strullu-Derrien, S. McLoughlin, M. Philippe, A. Mørk, D.G. Strullu:

Arthropod interactions with

bennettitalean roots in a Triassic permineralized peat from Hopen,

Svalbard.

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology,

Palaeoecology 348–349(2012), 45-58.

[2]

N.A. Jud, G.W. Rothwell, R.A. Stockey:

Paleoecological and phylogenetic implications of Saxicaulis

meckertii ... :

A bennettitalean stem from the Upper

Cretaceous ...

Int J. Plant Sci. 171(2010), 915-25.

[3] T.N. Taylor

et al.: Paleobotany. Elsevier 2009

|

|

18 18 |

18

18

18

18