Prototaxites

and Cosmochlaina:

no liverwort connection

A very peculiar hypothesis has been presented [1] as an explanation for

the big enigmatic fossil called Prototaxites.

This fossil has been

included into the chapter Enigmatic Organisms in [2] since it looks

like a tree trunk but does not consist of wood, and it lived in the

Silurian and Lower Devonian when plants on land did not exceed heights

of a few

centimeters.

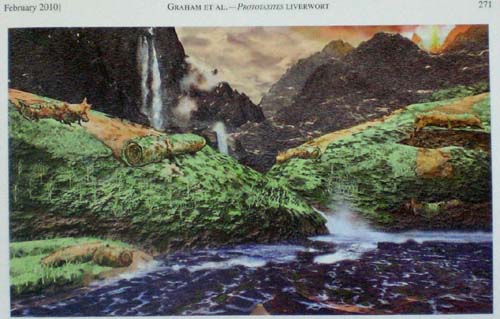

In order to obtain, in imagination, a big trunk-like

fossil from the humble vegetation, the authors [1] invoke the idea of

rolled-up mats. Liverwort mats on sloping rock surfaces are supposed to

curl in at the upper end and eventually start rolling down the slope as

pictured with artistic skill in Fig.1. Leaving aside the question how

all those carpet rolls could become so tightly wound that their

cross-sections remained nearly circular while lying around awaiting

silicification, one can challenge the hypothesis by starting from

the liverwort side of the problem. Small nematophytes recently found in the Rhynie chert

provide surprising insights.

Fig.1: Prototaxites

forming from liverwort rolls

as imagined by GRAHAM

et al. (2010) [1].

Fossil liverworts are known since the Upper

Middle Devonian [2]. In

order to have liverworts in the Silurian, the authors [1] had

re-interpreted Silurian cuticles known as Nematothallus

and

Cosmochlaina

(Fig.2), usually thought to belong to the nematophytes,

as

liverwort cuticles in a previous publication [3]. Recent finds of

nematophytes in Rhynie

chert provide contrary evidence [4]. A concise

version of the presentation [4], focused on the explanation of the

hitherto unexplained structure of the Nematothallus

cuticle, is given in Rhynie

Chert News 38.

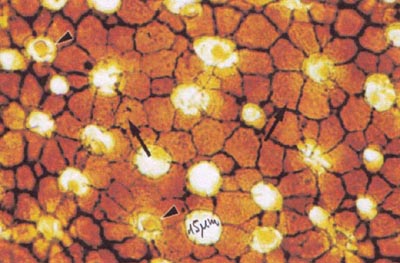

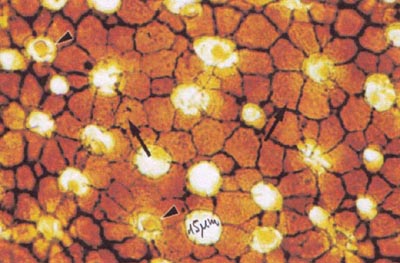

What remains to be done is to interpret the conspicuous pattern of Cosmochlaina

without resorting to liverworts. (According to [1], the arrows in Fig.2

indicate "pores surrounded by cell rosettes", which is shown to be a

misinterpretation in the following.)

Fig.2 (below) with detail:

Silurian cuticle Cosmochlaina,

re-interpreted in [1] as lower epidermis

tissue of liverworts with broken-off rhizoids but quite differently

interpreted here.

The

rather superficial similarity to the lower epidermis of liverworts with

broken-off rhizoids misled Graham

et al. [3] to the assumption that it

really is such. The polygonal meshes, cautiously called "entities" in

[5] but readily interpreted as cells in [3], should better give rise to

suspicion. Rhizoids grow from one cell each so that a rhizoid emerging

from 7 cells at once as in this picture (see detail) would

not

make sense. By carefully inspecting Fig.2 one finds more features of

the pattern which are hardly compatible with the notion of a cell

sheet. Here it is useful to know that what looks like a cellular

pattern could be a crack pattern, an idea which may suddenly remove

apparent absurdities and open other vistas. (For another case

of this

type, see Rhynie

Chert News 8.)

According to the

interpretation proposed here, Cosmochlaina

is a cuticle belonging to a

nematophyte as originally assumed. The round spots are the

cross-sections or ends of the tube-like filaments embedded in gel which

make up

the nematophyte. Hence, the old problem of how a nematophyte could

produce a cell sheet has vanished: There are no cells but only cracks.

The cracks could be due to shrinkage of the drying surface of the lump

of gel. The nematophyte could have released an organic substance which

accumulated on the gel surface, polymerized into a decay-resistent

cuticle as a protection against exsiccation, and thus preserved a

replica of the surface crack pattern.

Unexpectedly, an early paper on

Cosmochlaina

[5] supports the interpretation of Fig.2 as a crack pattern. There,

specimens are shown whose aspect differs much

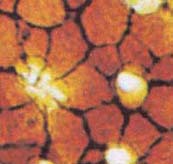

from Fig.2, the most often reproduced picture of this fossil: See Fig.3.

Fig.3 (right): Cosmochlaina

as it is seldom pictured [5]: no polygon pattern

but early stage of crack propagation.

Remarkable is the absence of the polygon pattern

which is often thought to be an inherent feature of

Cosmochlaina

but is not.

Apparently the cuticle in Fig.3 shows a very

early stage of crack pattern formation, with only a few short cracks

emerging from the tube cross-sections. The transition from individual

cracks to polygon patterns is not yet completely understood in fracture

mechanics but the

phenomenon as such is well known from various substances undergoing

shrinkage.

Annotation 2020: A

tendency of growing shrinkage cracks to form polygon patterns has been

demonstrated with fracture mechanical computations in [7].

Now that no evidence is left for Silurian liverworts in the disguise of

Cosmochlaina

and Nematothallus,

the liverwort hypothesis of

Prototaxites

lacks its main ingredient. Without any other vegetation

available for making carpet rolls from, Prototaxites

remains as

enigmatic as ever. (See also [6].)

H.-J. Weiss

2010 2020

[1] L.E.

Graham,

M.E. Cook, D.T. Hanson, K.B. Pigg, J.M. Graham :

Structural, physiological, and

stable carbon isotope

evidence that the enigmatic Paleozoic fossil Prototaxites formed

from

rolled liverwort mats.

Am. J. Bot.

97(2010), 268-275.

[2] T.N. Taylor,

E.L. Taylor, M. Krings : Paleobotany, Elsevier 2009,

p163.

[3] L.E. Graham,

L.W. Wilcox, M.E. Cook, P.G. Gensel

:

Resistant tissues of

modern marchantoid liverworts resemble enigmatic Early Paleozoic

microfossils.

Proc. Nat. Acad.

Sci., USA, 101(2004), 11025-29.

[4] H.-J. Weiss:

Nematothallus: How the filaments produced a cellular

cuticle. (Oral presentation)

8th European

Palaeobotany - Palynology Conference 2010, Budapest.

[5] D. Edwards :

Dispersed cuticles of putative non-vascular plants from

the Lower Devonian of Britain,

Bot. J. Linnean Soc.

93(1986), 259-75.

[6] H. Steur:

www.xs4all.nl/~steurh/

[7] M. Hofmann, R. Andersson, H.-A. Bahr, H.-J. Weiss, J. Nellesen: Why

Hexagonal Basalt Columns?

Phys.

Rev. Lett. 115, 154301 (2015)

|

|

41 |