A Lower Devonian alga resembling the

xanthophyte Botrydium

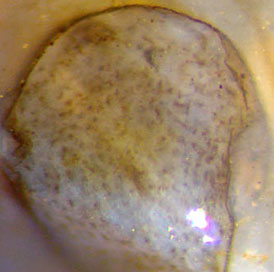

The

bunch of funnel-shaped organisms in a small sample of Rhynie chert

(Fig.1) has come as a surprise as it differs from any known fossil from

that site. Apparently it is neither land plant, green alga, fungus, nor

microbial formation.

It resembles a xanthophyte, and if it really is

one, it would be, according to [1] and other sources, the

first fossil xanthophyte ever seen, since "There are no positively

known fossils of the Xanthophyta, ...". To explain the

reason why, [1] is quoted here again: "It is likely that the lack

of a fossil record results more from the fact that their cyst

morphology is

poorly studied, rather than from a lack of preservation, since the

silicified cysts of this group ought to be found."

The

bunch of funnel-shaped organisms in a small sample of Rhynie chert

(Fig.1) has come as a surprise as it differs from any known fossil from

that site. Apparently it is neither land plant, green alga, fungus, nor

microbial formation.

It resembles a xanthophyte, and if it really is

one, it would be, according to [1] and other sources, the

first fossil xanthophyte ever seen, since "There are no positively

known fossils of the Xanthophyta, ...". To explain the

reason why, [1] is quoted here again: "It is likely that the lack

of a fossil record results more from the fact that their cyst

morphology is

poorly studied, rather than from a lack of preservation, since the

silicified cysts of this group ought to be found."

This plain situation, without any fossil xanthophytes

through the ages, has apparently ended

with the discovery of Palaeovaucheria

[3], an alga

more than twice as old as the Rhynie chert, interpreted as a

xanthophyte in a "Gongrosira

phase".

Disregarding that dubious fossil from the Proterozoic, one can assume

that the silicified cysts which ought to be found according to

[1] have been found now.

There are 8 funnel-shaped bags in this sample,

5 of which are seen here, more or less inclined towards the picture

plane. Because of this inclination, their bases

are deeper inside the sample and

therefore not seen.

Fig.1: Bunch of funnel-shaped bags seen at the edge of a Rhynie chert

fragment, resembling truncated cysts of the extant xanthophyte Botrydium. Width of

the picture 5mm.

From the outlines seen on the fracture faces it

may be concluded that the bags or cysts had nearly axial symmetry. One

of the bags,

2nd from the right, is the only one which had been subjected to

slight vertical compression, the result of which indicates that its

wall had

been very flexible and thin, estimated 1Ám or less. The

top of the other cysts is missing, broken off when the small fragment

was shaped by disintegration of the chert layer.

Two not quite plane fracture faces meet at

an angle of about 100░ in Fig.1, hence their common (slightly rounded)

edge is not quite straight, seen as a bright line

due to reflection of incident light. The picture plane has been chosen

such that it

essentially coincides with that fracture face which reveals most of the

bags, either as sections or as views through the transparent chalzedony.

Incidentally the two fracture faces are in such positions that they

permit

inspection of the bag on the right from different directions. Since

this bag is slightly deformed, the contour on one sample face is

irregular (Fig.2)

but not smoothly curved as it would be expected from a plane cut of an

inverted cone. Above the rounded edge in Fig.2,

which is marked by the bright reflections, the other face offers

a top view with partially circular outline (Fig.3),

except for the broken-off part. (To obtain a 3D-imagination, compare

Fig.2 and Fig.3, with Fig.1.)

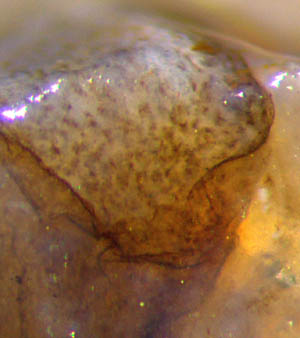

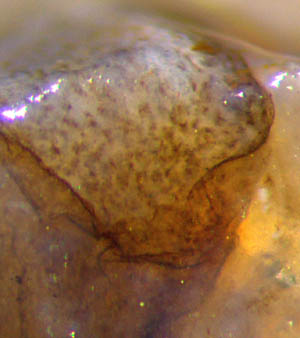

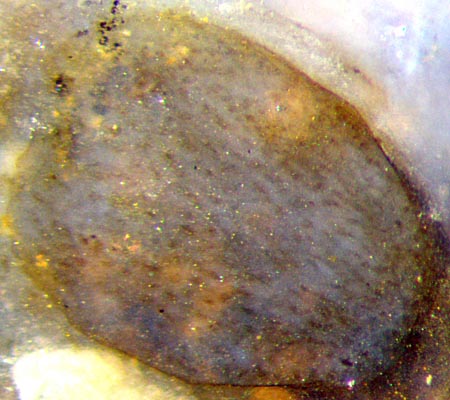

Fig.2 (far left): Detail on the sample front face cutting

sideways into

the funnel-shaped bag on the right in Fig.1, irregular outline due to

local deformation before silicification. Width of the picture 0.8mm.

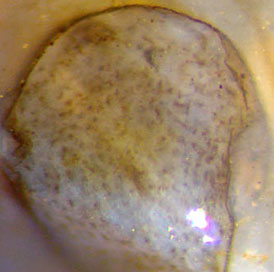

Fig.3: Top view of the truncated cyst seen sideways in Fig.2. Width

of the picture 0.73mm.

The above claim of the discovery of a fossil

xanthophyte is substantiated by details from these images. An epidermis

is conspicuously absent, and so is any tissue, although the

interior of some bags is clearly seen to be filled rather evenly with

fuzzy dots of about 20Ám. Other bags are empty. This is compatible with

Botrydium,

which is characterized by large numbers of nuclei and

chromatophores within a giant cell attached to moist soil [2]. When the

place is flooded, the nuclei and plasma turn into zoospores which

escape through an opening. Judging from the layering of the Rhynie

chert, flooding had occured repeatedly in the habitat which brought

forth the chert, which may

explain why some of the bags in Fig.1 are empty.

The apparently

shapeless dots in Figs.2-4 had possibly been in some stages of

transformation into

zoospores when being silicified. As another option, the giant

cells of Botrydium

can become empty by producing and releasing gametes [2].

The apparently

shapeless dots in Figs.2-4 had possibly been in some stages of

transformation into

zoospores when being silicified. As another option, the giant

cells of Botrydium

can become empty by producing and releasing gametes [2].

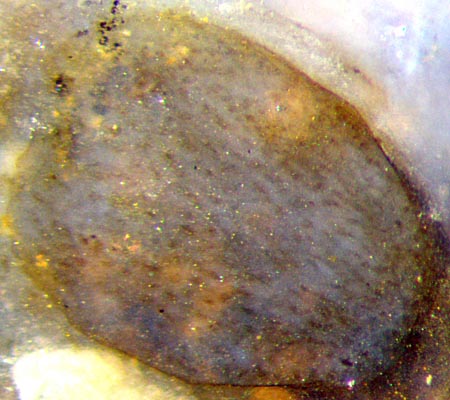

Fig.4 (right): One of the bags in Rhynie chert resembling cysts

of the extant xanthophyte Botrydium,

inclined section on the fracture face in

Fig.1 below left, seen here filled with nuclei (and

chromatophores ?).

Width of the bag 0.75mm.

Preservation in Rhynie chert had been governed by the competition

of decay and silicification. In the present case, another process had

also been relevant: Flooding could have initiated the formation and

release of zoospores or

gametes, similar as with extant Botrydium

[2]. Silicification interfered with this process so that the motile

unicells managed to escape from some of the tubes in Fig.1 before

silica gel formation but not from others. Hence, one should anticipate

the presence of fossil bunches of empty cysts which could easily be

misinterpreted as land plant cuticles.

Finally it can be assumed that, disregarding the

Proterozoic, the above images show the

first

fossil

xanthophyte, representing a 400-million-years-old one out of

this class of algae with about 600 extant species [1].

Photographs taken from the raw surface of a Rhynie

chert fragment of 20g found by Sieglinde

Weiss in 2014, stored under the

label Rh2/200.

H.-J.

Weiss

2014, modified

2016, 2020

[1] Introduction to the Xanthophyta,

www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/chromista/xanthophyta.html

[2] R. E. Lee: Phycology, p417. Cambridge 2008.

[3] N.J. Butterfield: A vaucheriacean alga

from the middle Neoproterozoic of Spitsbergen.

Paleobotany 30(2004), 231-252.

|

|

69 |

The

bunch of funnel-shaped organisms in a small sample of Rhynie chert

(Fig.1) has come as a surprise as it differs from any known fossil from

that site. Apparently it is neither land plant, green alga, fungus, nor

microbial formation.

It resembles a xanthophyte, and if it really is

one, it would be, according to [1] and other sources, the

first fossil xanthophyte ever seen, since "There are no positively

known fossils of the Xanthophyta, ...". To explain the

reason why, [1] is quoted here again: "It is likely that the lack

of a fossil record results more from the fact that their cyst

morphology is

poorly studied, rather than from a lack of preservation, since the

silicified cysts of this group ought to be found."

The

bunch of funnel-shaped organisms in a small sample of Rhynie chert

(Fig.1) has come as a surprise as it differs from any known fossil from

that site. Apparently it is neither land plant, green alga, fungus, nor

microbial formation.

It resembles a xanthophyte, and if it really is

one, it would be, according to [1] and other sources, the

first fossil xanthophyte ever seen, since "There are no positively

known fossils of the Xanthophyta, ...". To explain the

reason why, [1] is quoted here again: "It is likely that the lack

of a fossil record results more from the fact that their cyst

morphology is

poorly studied, rather than from a lack of preservation, since the

silicified cysts of this group ought to be found."

The apparently

shapeless dots in Figs.2-4 had possibly been in some stages of

transformation into

zoospores when being silicified. As another option, the giant

cells of Botrydium

can become empty by producing and releasing gametes [2].

The apparently

shapeless dots in Figs.2-4 had possibly been in some stages of

transformation into

zoospores when being silicified. As another option, the giant

cells of Botrydium

can become empty by producing and releasing gametes [2].