Erroneous and other views on a Rhynie

chert plant

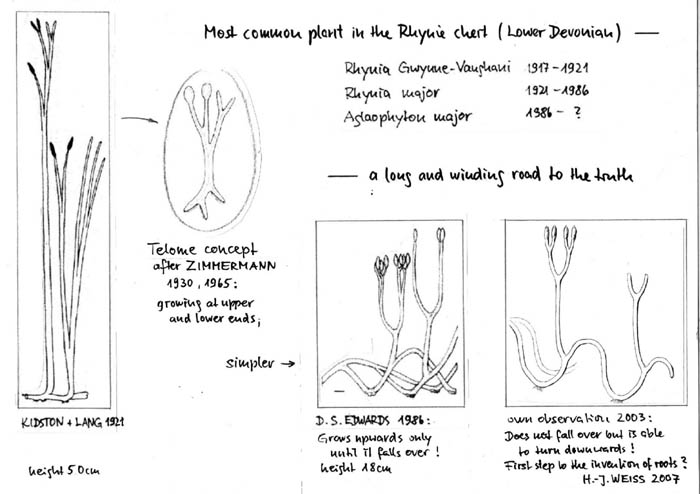

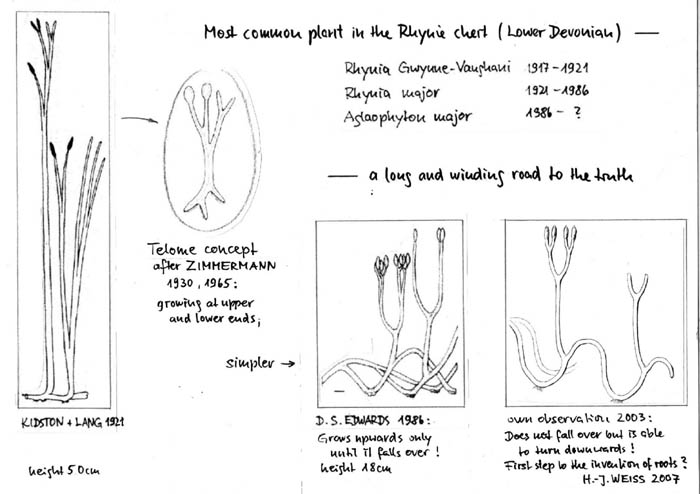

In the first paper on Rhynie chert plants [1], the two species now

known as Aglaophyton

major and Rhynia

gwynne-vaughani were treated as

one and given the latter name. When it became apparent that there were

two, the bigger one was named Rhynia

major. It was thought to be bigger

than it really was, and its reconstruction was rather different from

the present ones. (See drawing below left.)

It is one of the crazy things happening sometimes that the poor

reconstruction raised a great idea in the mind of the German

paleobotanist Zimmernann

[2]. The result was his Telome Theory of plant

evolution, which became, and still is, widely accepted but also much

disputed. His construct of an archetypal plant was meant to represent

the simplest early land plants. So it is surprising to see that the

real plant is even simpler than the model plant derived from it.

According to D.S.

Edwards

it grows in only one direction, which is

upward, until it falls over, grows rhizoids where it touches the

ground, and turns upwards again [3]. Falling over is not quite a bad

idea as the plant would finally do so if it had not invented a more

clever option which consists in turning downwards intentionally. The

latter is obvious from the observation that the radius of curvature of

the downward bend is as small as about 1.5cm or even smaller.

It is one of the crazy things happening sometimes that the poor

reconstruction raised a great idea in the mind of the German

paleobotanist Zimmernann

[2]. The result was his Telome Theory of plant

evolution, which became, and still is, widely accepted but also much

disputed. His construct of an archetypal plant was meant to represent

the simplest early land plants. So it is surprising to see that the

real plant is even simpler than the model plant derived from it.

According to D.S.

Edwards

it grows in only one direction, which is

upward, until it falls over, grows rhizoids where it touches the

ground, and turns upwards again [3]. Falling over is not quite a bad

idea as the plant would finally do so if it had not invented a more

clever option which consists in turning downwards intentionally. The

latter is obvious from the observation that the radius of curvature of

the downward bend is as small as about 1.5cm or even smaller.

As indicated in the drawing on the right, the

overall shape may simply

be dominated by repeated forking*, with one or two prongs of the lower forks

growing downwards on purpose, touching the ground, etc. This reminds

one strongly of the habit of roots. Hence, what we see here might be a

glimpse at roots in the making.

As pointed out by Dianne Edwards [4], the change of name into Aglaophyton by David

S. Edwards [3] was not well justified and the placement outside the tracheophytes by others is questionable.

The reason why it took a long time to find out the overall shape

of the most abundant Rhynie plant is the preservation in chert, which

provides tiny detail even inside cells but does not easily reveal the

large-scale structure. The chert is essentially isotropic and hence

does not show cleavage planes with compressions of whole plants.

Reconstruction by cutting thin slabs or by successive removal of chert

is laborious since fresh and more or less decayed specimens are

usually silicified in a confusing tangle.

In

view of this, it would not be surprising if the

reconstruction of Aglaophyton

had to be further modified.

H.-J.

Weiss

2007, emended 2014

*According to other and own observations,

this plant is able to branch not only by forking but in the lower parts

also by lateral buds growing into shoots with rhizoids. (See Rhynie

Chert News 52). Hence,

this plant may be more tangled near the ground than suggested by the

drawing on the right which is to visualize the principle of downward

growth. As another observation, the upward bend is usually not nicely

U-shaped, as already indicated in the 1986 drawing.

[1] R.

Kidston, W.H. Lang

: On Old Red Sandstone plants

showing structure from the Rhynie Chert bed, Part I,

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh 51(1917),

761-84.

[2] W.

Zimmermann

: Die Phylogenie der Pflanzen, 1930, 2.

Aufl. 1959.

[3] David

S. Edwards, Aglaophyton

major, a non-vascular land-plant from the Devonian Rhynie

Chert,

Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 93(1986), 173-204.

[4] Dianne Edwards: Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfied cherts,

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 94(2004 for 2003), 397-410.

|

|

17 |

It is one of the crazy things happening sometimes that the poor

reconstruction raised a great idea in the mind of the German

paleobotanist Zimmernann

[2]. The result was his Telome Theory of plant

evolution, which became, and still is, widely accepted but also much

disputed. His construct of an archetypal plant was meant to represent

the simplest early land plants. So it is surprising to see that the

real plant is even simpler than the model plant derived from it.

According to D.S.

Edwards

it grows in only one direction, which is

upward, until it falls over, grows rhizoids where it touches the

ground, and turns upwards again [3]. Falling over is not quite a bad

idea as the plant would finally do so if it had not invented a more

clever option which consists in turning downwards intentionally. The

latter is obvious from the observation that the radius of curvature of

the downward bend is as small as about 1.5cm or even smaller.

It is one of the crazy things happening sometimes that the poor

reconstruction raised a great idea in the mind of the German

paleobotanist Zimmernann

[2]. The result was his Telome Theory of plant

evolution, which became, and still is, widely accepted but also much

disputed. His construct of an archetypal plant was meant to represent

the simplest early land plants. So it is surprising to see that the

real plant is even simpler than the model plant derived from it.

According to D.S.

Edwards

it grows in only one direction, which is

upward, until it falls over, grows rhizoids where it touches the

ground, and turns upwards again [3]. Falling over is not quite a bad

idea as the plant would finally do so if it had not invented a more

clever option which consists in turning downwards intentionally. The

latter is obvious from the observation that the radius of curvature of

the downward bend is as small as about 1.5cm or even smaller.