A Devonian plant that would not fit in

Fossil finds which do not seem to fit to known species are not uncommon

and keep the palaeontologists wondering. Most often it is found out

where they fit in after all, otherwise they may indicate the presence

of something

new. Really intriguing are the nematophytes, which have got

names but have not yet got a branch on the Tree of Life. The

Lower Devonian Rhynie chert has provided some, including new

ones. The Rhynie chert is expected to yield more surprises, and here is

another one which awaits interpretation.

Fig.1: Unknown fossil in Rhynie chert with granular aspect. Width of

the picture 9.5mm.

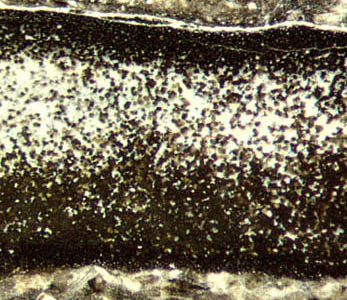

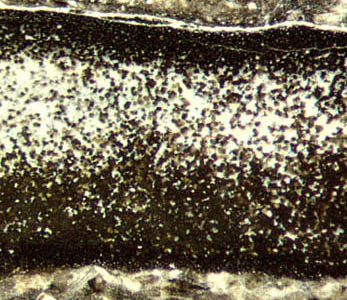

Fig.2 (below): Detail of Fig.1. Width of the picture 1.5mm.

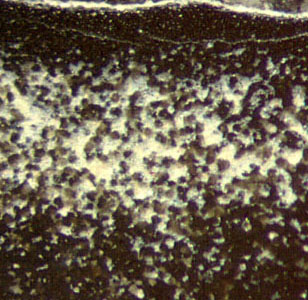

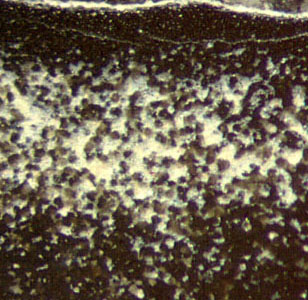

Fig.3 (left): Angular grains of unknown origin, detail

of Fig.1. Width of the picture 0.83mm.

The

plant or plant parts presented here look like a bag filled with grains

(Figs.1,2).

Their partially straight contours could be crystal faces or replicas of

plane cell walls. Apparently, silicification has produced quartz powder

in addition to the compact grains, providing good optical contrast.

The dark grains

show a slight tendency of being arranged in chains, as seen

in Fig.3 at

some place on

the right, for example. This indicates that a process spreading from

cell to cell

may have affected the silification of the interior. Phenomena of

such kind, perhaps mediated by some rot fungus, have

produced the cell-size clots or angular grains repeatedly

misinterpreted as mite coprolites.

The grain size of 20...35Ám

is smaller than the cell sizes of any

of the 7 vascular plants hitherto discovered in the Rhynie chert, and

also smaller than the "coprolites"

found in

petrified wood.

The

black appearance is brought about by two effects: The transparent

grains let the light pass into depth and therefore look much

darker

than the white powdery quartz, and some have

black

inclusions of decayed organic matter. Near the surface of the grain bag

the dark grains are so crowded

that one cannot see whether or not the plant had an epidermis.

There

is a small spot of decayed and vanished tissue where the former surface

is faintly indicated by a thin dark line (Fig.4). Such line

is also

seen in some places on the other half of the cut specimen. The thin

lines along parts of the contour might be the remains of a

cuticle on an epidermis.

There

is a small spot of decayed and vanished tissue where the former surface

is faintly indicated by a thin dark line (Fig.4). Such line

is also

seen in some places on the other half of the cut specimen. The thin

lines along parts of the contour might be the remains of a

cuticle on an epidermis.

Fig.4 (left): Cuticle (?) seen as a dark line covering

a hole under the surface (below left in

Fig.1).

Fig.5 (right): Squeezed end of the bag in Fig.1 or end of stalk with

holdfast ? Width of the picture 0.7mm.

There

is one feature in Fig.1 which is either highly significant or a mere

artefact due to partial decay and compression: The bag of more than 1mm

thickness suddenly narrows into an indistinctly seen

extension to the right, poorly silicified and traversed by

cracks. It resembles a stalk with a (tripartite

?) foot or holdfast, width 0.6mm, at its end (Fig.5).

As the bag is also seen on the other side of the cut gap

of 1mm or more, and with the

surfaces of the halves standing nearly perpendicular on the cut

faces, one can conclude that what

is seen in Fig.1 is a lengthwise section of a bag of little more than 1mm

thickness and at least 3mm width. If the narrow extension really were a

stalk, it would be ribbon-like.

The fact that no

indication of vascular tissue is seen on either half of the divided bag

does not mean

there is none but it suggests that possibly there is none.

The absence of hyphae and tubes excludes any affiliation

with fungi or

nematophytes. The presence of a cuticle (Fig.4) does not necessarily

indicate a land plant. Organisms living in an

aquatic

habitat which repeatedly falls dry may develop a cuticle, as it is

known from nematophytes. The habitat

which turned into the Rhynie chert

by silicification harboured aquatic and subareal plants,

fungi,

and creatures.

At a vertical distance of about 3cm below Fig.1, lots of squeezed and a

few well

preserved Rhynia

sections are seen, together with several charophyte specimens

resembling Palaeonitella,

indicating subaerial and submerged conditions at times.

A plant with bag-like body, stipe, and holdfast suggests

comparison with the recent Brown Alga Laminaria. The

comparison leads to a bigger and a smaller problem: This fossil is more

than twice as old as the allegedly first Brown Algae [1].

Hence, there must have been algae with the aspect of Brown Algae long

before, which poses the problem of where to place them on the

phylogenetic tree.

The fact that this alga had lived in the

Devonian freshwater-dominated habitat at Rhynie does not preclude an

interpretation as a precursor of Brown Algae

since

it is known that among the numerous extant Brown Alga species there

is

a

small fraction of freshwater species [2]. This

small alga could have been a freshwater

Brown Alga of its time,

which would be the only one found hitherto.

Although a final interpretation of the fossil

has to be left to those

who

might find more specimens of this kind sometime or perhaps have a

bright idea just now, a few tentative conclusions suggested by the

observations have been presented here.

Sample: Rh22/1 (0.21kg), found by Sieglinde Weiss at

Castlehill in 2009.

H.-J.

Weiss

2013, modified in

2021

[1] Th. Silberfeld

et al.: A multi-locus

time-calibrated phylogeny of the brown algae

... Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 56 (2010) 659–674.

[2] J.D. Wehr:

Freshwater Algae of North America, Chapter 19,

Brown Algae, 2014, Acad. Press.

|

|

50 |

There

is a small spot of decayed and vanished tissue where the former surface

is faintly indicated by a thin dark line (Fig.4). Such line

is also

seen in some places on the other half of the cut specimen. The thin

lines along parts of the contour might be the remains of a

cuticle on an epidermis.

There

is a small spot of decayed and vanished tissue where the former surface

is faintly indicated by a thin dark line (Fig.4). Such line

is also

seen in some places on the other half of the cut specimen. The thin

lines along parts of the contour might be the remains of a

cuticle on an epidermis.