A pattern of questionable origin

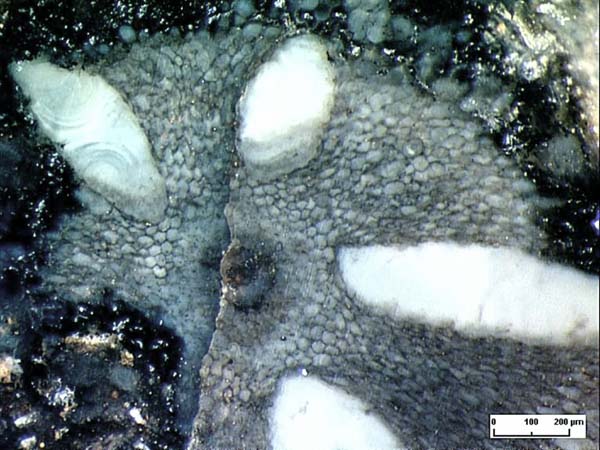

A conspicuous pattern of radially arranged oblong voids is occasionally

found on plant cross-sections in the Rhynie chert

(Fig. 1). The pattern is well known, for example, from the most

abundant Rhynie plant, Aglaophyton, and has also been found in the

rarest one, Ventarura [1], which belongs to a quite different phylum.

This suggests the existence of a common cause not inherent in the

nature of the plant.

Fig.1: Pattern of voids in a cross

section with otherwise

healthy aspect, probably Rhynia.

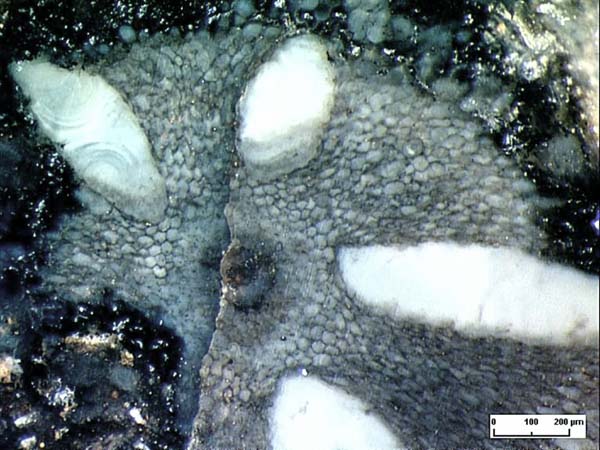

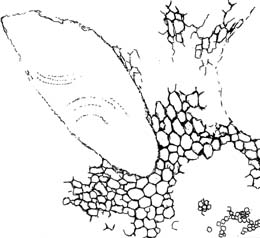

Fig.2: Pattern of large voids in a

cross section, probably

of Aglaophyton. Photographs: H. Sahm

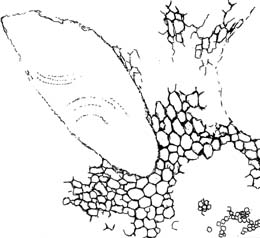

Fig.3: Detail from Fig.2, no indication of decay or rupture

at the apex of the void.

Fig.3: Detail from Fig.2, no indication of decay or rupture

at the apex of the void.

In [2] it is assumed that the void pattern is due

to some decay process resulting in the formation of shrinkage cracks.

This assumption was seemingly confirmed by the observation that the

pattern had been found in decaying axes but not in fresh ones.

Now it appears that the assumption can be refuted by evidence from only

one sample (Fig.2). Although the plant tissue is not completely

preserved on the whole cross section it is seen that the cells near the

alleged shrinkage crack tip are neither decayed nor torn, they look

rather healthy instead (Figs. 2,3). So the

assumption seems justified that the voids had been there

in the living plant *, which requires a not so simple explanation.

The two chalcedony spherulites faintly seen in one of the holes in Fig.

2 could not have been involved in the void formation process: They must

have formed in the already existing void. There is a most likely

explanation based on the following facts:

(1) Fungus infection can cause abnormal growth in

extant plants.

(2) Fungus infection had been identified as a

cause of bloating in Rhynie chert plants [3].

(3) Often Rhynie chert plants are heavily infected

with various fungus species [4].

Hence it can be assumed that the void

pattern was formed in the living plant, with abnormal growth under the

influence of substances released by some fungus hidden in the tissue.

There is room for wild speculation concerning the effect or purpose of

these large voids. They do not seem occupied by the ubiquitous fungus

hyphae

normally seen in the Rhynie chert. If some fungus created them in the

living plant, one might expect that it profited from them in some

obscure way. Also the plant could have profited from the voids as it

could make a larger diameter

with a given amount of tissue and thus become mechanically more

stable. This would be a bizarre type of interaction for mutual benefit.

H.-J. Weiss

2005

[1] C.L.

Powell, D. Edwards, N.H. Trewin : A new

vascular plant from the Lower Devonian Windyfield chert, Rhynie, NE

Scotland.

Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh, Earth Sci.

90(2000 for 1999), 331-349.

[2] www.abdn.ac.uk/rhynie

[3] T.N.

Taylor, W. Remy, H. Hass

: Parasitism in a

400-million-year-old green alga,

Nature 357(1992), 493-494.

[4] T.N. Taylor,

E.L. Taylor :

The Rhynie chert ecosystem: A model for understanding fungal

interactions,

in:

Microbial Endophytes, eds. Ch.W.

Bacon, J.F. White Jr.; Marcel Dekker Inc.

2000.

* Annotation 2014, 2017: For related evidence see Rhynie

Chert News 21, 54, 117.

|

|

4 |

Fig.3: Detail from Fig.2, no indication of decay or rupture

at the apex of the void.

Fig.3: Detail from Fig.2, no indication of decay or rupture

at the apex of the void.