Nematophytes in gel

Fossil nematophytes, like any fossils preserved in chert, underwent

transient stages of being embedded in and permeated by silica gel,

governed by processes more or less well understood, which will not be

considered here. This contribution is about organic gel produced by the

organisms themselves for multiple protection. After silicification, the

organic gel is usually no more seen but its former

presence may be deduced from details seen in the chert (Fig.1).

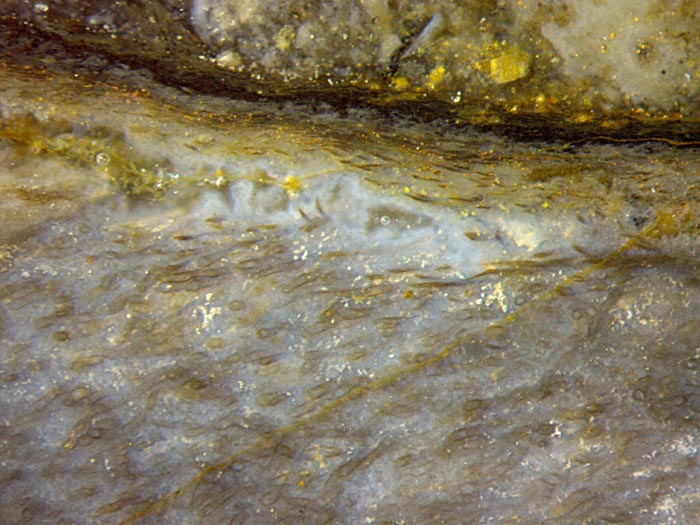

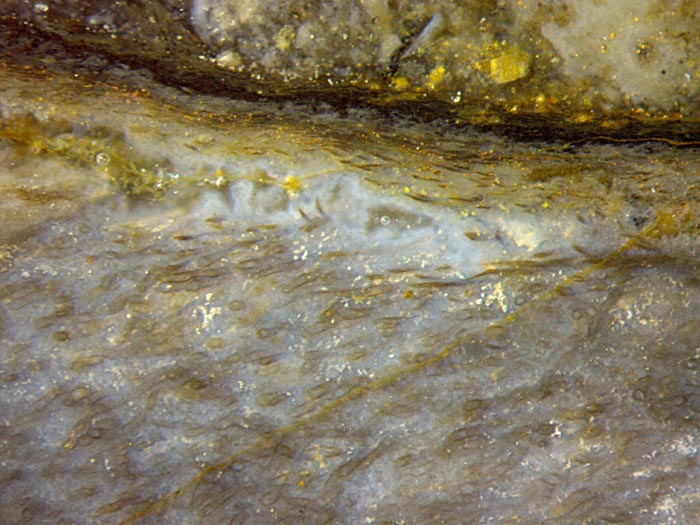

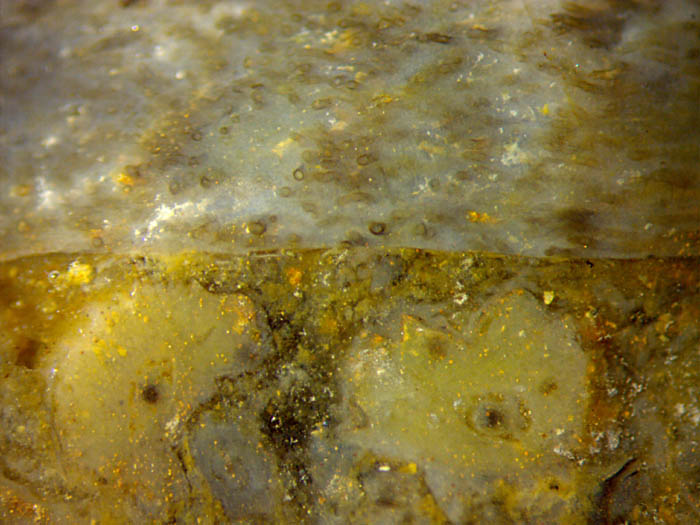

Fig.1: Rhynie Chert, raw sample surface, old fracture face of the chert layer with two types of chert: nematophyte above, silicified earlier than the swamp matter

including degraded plant cross-sections below, tightly fused into one solid block now.

Width of images: 4.3mm.

This

image may be confusing and enigmatic

at first sight. It is a natural combination of two quite different

parts of chert. The upper half is a nematophyte consisting of

randomly arranged but partially aligned tubes in bluish chalcedony. The

nearly horizontal line in the

image indicates a smooth fracture face unlike that of a felt of tubes

or of a fibrous composite material. Hence, the nematophyte had broken

like a compact material, which implies that it had been in some

advanced state of silicification. The fragment got into

the muddy water with mineral debris and flooded land plants below,

now

largely degraded. Silicification proceeded until finally all had turned

into

solid chert.

Apart

from the fossil content, another difference between the halves of the

picture is obvious: Contrary to the abundant debris and mineral

precipitates below, the space between the tubes above is rather clean.

The small white specks are no inclusions but the result of

recrystallisation in chalcedony. The absence of debris between the

tubes

indicates the presence of organic gel which precluded any dirt from

entering.

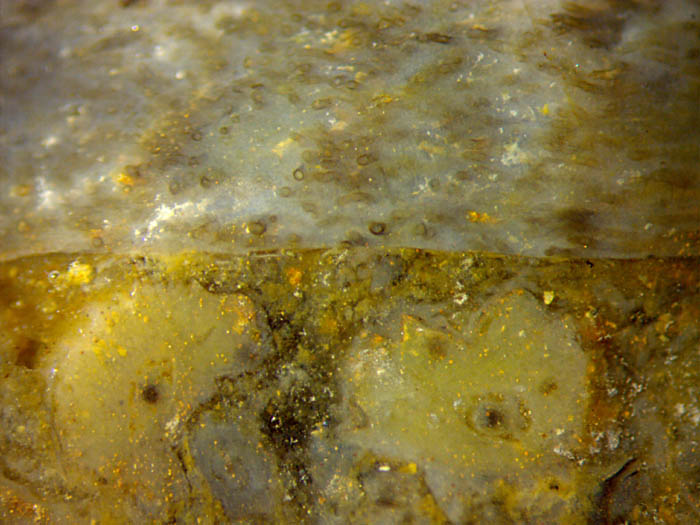

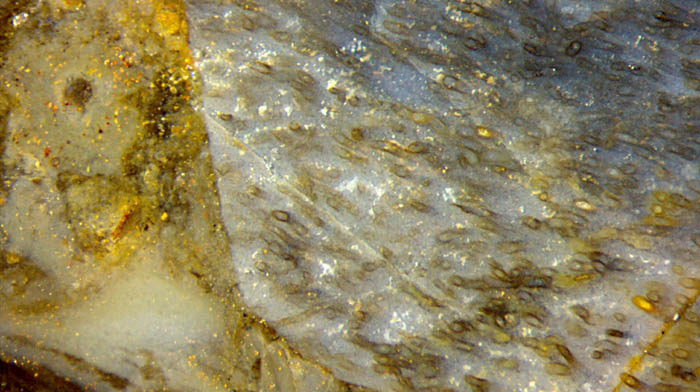

Essentially the same is seen in Fig.2. Here, the crack goes athwart the

texture of the felt. Again the crack face is smooth,

without tube ends sticking out. Hence the nematophyte as a whole must

have been mechanically homogeneous when it broke, with tubes and matrix

thoroughly silicified so that the felt-like structure did not affect

the crack propagation.

There is no indication concerning the cause

of the fracture of the nematophyte while the swamp matter was still

fluid. It is known that organic matter gets silicified faster

than the surrounding water and thus can break when bent or torn.

Perhaps the organic gel assumed to fill the space between the tubes

triggers the early formation of silica gel which tends to become more

and more solid by uptake of silica so that it can break like a brittle solid when strained.

Fig.2: Two types of chert combined

in one sample: fragment from brittle fracture of early

silicified nematophyte (right) next to fluid swamp matter with degraded

plants (left) silicified later. Cut face of the sample in Fig.1.

Fig.2: Two types of chert combined

in one sample: fragment from brittle fracture of early

silicified nematophyte (right) next to fluid swamp matter with degraded

plants (left) silicified later. Cut face of the sample in Fig.1.

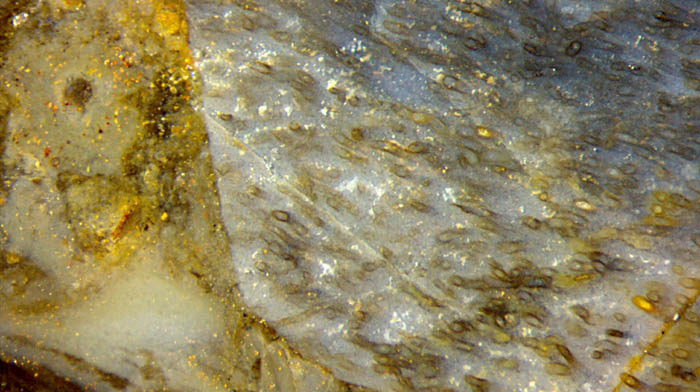

In addition to the advantages of organic gel for life in water,

which is keeping things together, keeping dirt away, and protecting

against attack, gel serves as a means of survival of watery

organisms under subaerial conditions. The present sample offers

evidence that nematophytes may have applied this survival technique, as

suggested by Fig.3. This nematophyte had lived as a felt of tubes in a

lump of gel with

unknown overall size and shape, either in water or on moist ground, or

in a periodically changing habitat. During a prolonged dry period the

lump with tubes dried up at the surface and shrunk, which proceeded

into some depth. Thereby the limp tubes collapsed so that

they are seen as mere narrow streaks in the affected region of the lump

which forms a kind of cortex protecting the bulk from drought. No signs

of exsiccation are visible below.

The protective effect seems to have been limited by

internal stresses causing the hardened crust to detach and peel off. In Fig.3 it

adheres to the bulk on the right but becomes increasingly detached

towards the left.

Finally

the slightly damaged lump must have become inundated and silicified

while lying in the muddy water together with mineral debris and

degraded land plants, as also seen in Fig.3.

Fig.3 (below): Nematophyte as a lump of gel dried and shrunk to some

depth,

thus forming a dark protective layer against exsiccation of the bulk, seen here on the raw sample surface, old fracture face of the chert layer.

Among numerous

own samples of Rhynie chert found since 1998 there were

only 9 with nematophytes,

among them the well-known spherical Pachytheca (one

sample with one specimen) and the spiralling Nematoplexus,

with tubes distinctly larger than originally described, in 4 chert

samples. Less certain is the interpretation of

a rather well preserved nematophyte in another sample as Nematophyton

taiti [1].

Three more samples contain nematophytes differing

much from the known ones so

that they might represent 3 new species. Obviously they are

very rare, otherwise they would have been found in more than one chert

sample each.

Apparently

there had been organic gel between the tubes in every one of the

nematophytes mentioned here.

The lump of gel in Fig.3 with a dried-up, shrunken, and

possibly hardened layer along the surface seems to provide the most

convincing evidence that nematophytes might have been able to survive

or temporarily live under subaerial or dry conditions, as proposed in

[2,3]. Now that we

see them thoroughly silicified, we can conclude that they must have

been flooded with silica-rich water. There they became silicified

sooner

than the water since they broke like a solid material while the surrounding water was still

fluid and got silicified later, as suggested by Figs.1,2.

Sample

Rh13/7 (0.25kg), described in Rhynie

Chert News 13,

found by Sieglinde

Weiss in 2005.

Part 1: Fig.3; Part 2: Fig.1,2.

H.-J.

Weiss

2016 2020

[1] R.

Kidston, W.H. Lang : On Old Red Sandstone

plants showing structure ...,

Part V, Trans. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh 52

(1921),

855-902.

[2] P.K.

Strother: Clarification of the genus Nematothallus

Lang,

J.Paleont. 67(1993), 1090-94.

[3] www.abdn.ac.uk/rhynie

|

|

98 |

Fig.2: Two types of chert combined

in one sample: fragment from brittle fracture of early

silicified nematophyte (right) next to fluid swamp matter with degraded

plants (left) silicified later. Cut face of the sample in Fig.1.

Fig.2: Two types of chert combined

in one sample: fragment from brittle fracture of early

silicified nematophyte (right) next to fluid swamp matter with degraded

plants (left) silicified later. Cut face of the sample in Fig.1.