Trichopherophyton

aspects

Trichopherophyton

aspects

Considering the conspicuous feature of the less common but not quite

rare "hair-bearing plant", the

slender pointed bristles (Figs.1,2) whose length can exceed 1.5mm, one wonders why this plant had not been

discovered

earlier in the Rhynie chert [1]. There are possible reasons:

-

Apparently the bristles were borne as a protection against spore eaters only on the upper parts of

the plant which became less often silicified than the submerged parts.

Hence the latter (Figs.3,4) are less

easily recognized as Trichopherophyton.

- Trichopherophyton

seems to be prone to quick decay, except for the xylem strands and

sporangia, which are

not easily recognized when found scattered in the chert.

Fig.1: Trichopherophyton,

literally "hair-bearing plant", shoot

tip silicified while lying in water. (See big swamp gas

bubble below and small level bands indicating horizontal direction below

left.) The shoot seems to dive into the picture plane

towards the left, winding such that a bunch of bristles at the

very tip are directed out of the

picture plane towards the observer and thus are

seen in cross-section. Width of the picture about 7mm.

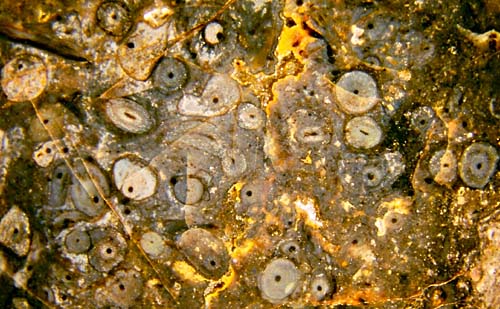

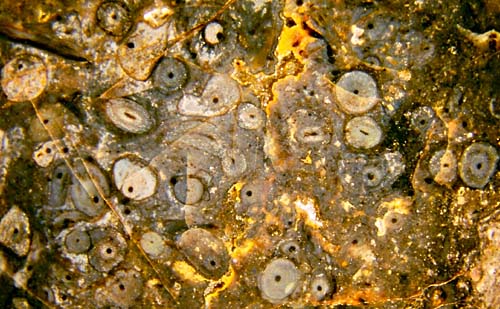

Fig.3 (below): Numerous Trichopherophyton

cross-sections

without bristles, width of

the picture 18mm.

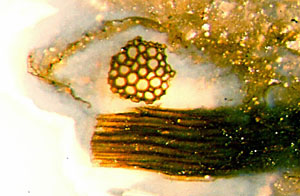

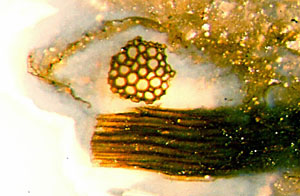

Fig.2 (right): Rare view from inside a Trichopherophyton

shoot into the bristles which are seen here as hollow cones with a

dark

dot of shrunken cell content.

Fig.2 (right): Rare view from inside a Trichopherophyton

shoot into the bristles which are seen here as hollow cones with a

dark

dot of shrunken cell content.

Fig.4 (middle): Trichopherophyton

cross-section,

width 1.5mm,

with uncommonly distinct aspect

of the different tissues.

Fig.5 (right): Trichopherophyton

cross-section,

width 1mm,

grown inside an older one.

The question arises how to recognize

the "hair bearing plant" when there are no bristly shoots. Depending on

the

state of preservation, the problem is more or less difficult. A rough

rule may apply here. If any three of the features listed below are

observed, it is very probably

Trichopherophyton:

(1) circular sections, mostly 1-2(-2.5)mm

across, without occasional warts on the surface,

(2) persistent xylem, seen as

dark strands (Figs.3-6) or as conspicuous sections as in Fig.6,

(3) scalariform pattern on the tracheid walls (Fig.7),

(4) light-coloured concentric region as in Figs.4,8,

(5) new shoots developing inside older ones

(Fig.5, close-up here),

(6) detached bristles somewhere in the sample,

(7) sporangia sections of various shape, never circular, (see

Rhynie

Chert News 22).

Fig.6 (far left): Trichopherophyton xylem

fragments, cross-section 0.16mm.

Fig.6 (far left): Trichopherophyton xylem

fragments, cross-section 0.16mm.

Fig.7: Scalariform pattern faintly seen in the tracheids of

the xylem strand. The divergence of the tracheids is due to the forking

of the strand.

Fig.8 (below right): Trichopherophyton

cut

lengthwise with light-coloured tissue (phloem ?) around the dark xylem

strand of 0.3mm

width. (Note also the small bluish level fill on the

left.)

If one or more of the above features are met, one should first

make sure

that there are no features suggesting the presence of other species. (For example, (1)

combined with a wart-like outgrowth on one of the circular sections

would mean it is Rhynia.

Diameters exceeding 3mm would rule out Trichopherophyton,

etc.) Then one should

carefully inspect every inch of the sample for hidden sections with

bristles attached. In case of (5), one can be quite sure that it is

either Trichopherophyton

or Ventarura, another zosterophyll.

In the absence of fragments of the upper part of Ventarura with the

characteristic persistent tube (previously thought to be sclerenchyma) it may be difficult to tell the two

species apart.

In

view of the fact that all pictures have been taken with incident light on arbitrarily chosen cut faces,

what is seen in Fig.6 is an extremely improbable configuration: By

queer coincidence, a xylem fragment had been cut exactly across in such

a way that only a short section of a few dozen micrometers extends into depth. Against

the scattered light from the surrounding translucent

chalcedony, it looks like a piece of lace illuminated from behind. The

dark xylem fragment seen below is positioned such that it had been cut

nearly lengthwise. Considering that the fragments do not belong to any

one of the common plants in the chert but to Trichopherophyton, which had first been described as late as 1991, this image is really awe-inspiring.

H.-J. Weiss

2012, emended 2013, 2015

[1] A.G.

Lyon,

D. Edwards: The first zosterophyll from the

Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert,

Trans. Roy. Soc.

Edinburgh, Earth Sciences, 82(1991), 323-332.

|

|

49 |

Trichopherophyton

aspects

Trichopherophyton

aspects

Fig.2 (right): Rare view from inside a Trichopherophyton

shoot into the bristles which are seen here as hollow cones with a

dark

dot of shrunken cell content.

Fig.2 (right): Rare view from inside a Trichopherophyton

shoot into the bristles which are seen here as hollow cones with a

dark

dot of shrunken cell content.

Fig.6 (far left): Trichopherophyton xylem

fragments, cross-section 0.16mm.

Fig.6 (far left): Trichopherophyton xylem

fragments, cross-section 0.16mm.