Croftalania

images

Picturesque fossil cyanobacteria are seldom

seen. The Rhynie

chert, which is famous for its often well preserved Lower Devonian

organisms, offers such, too. The filamentous cyanobacterium Croftalania [1],

when

grown in dense bunches on substrates, can make fanciful appearances [2 ,3].

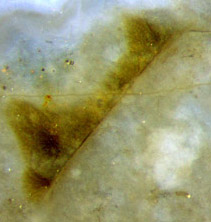

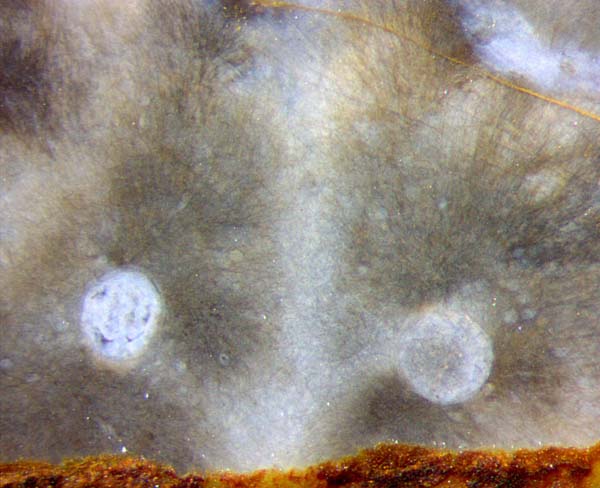

Fig.1: Croftalania

tufts on agate in Rhynie chert.

Width of the picture 8.6mm.

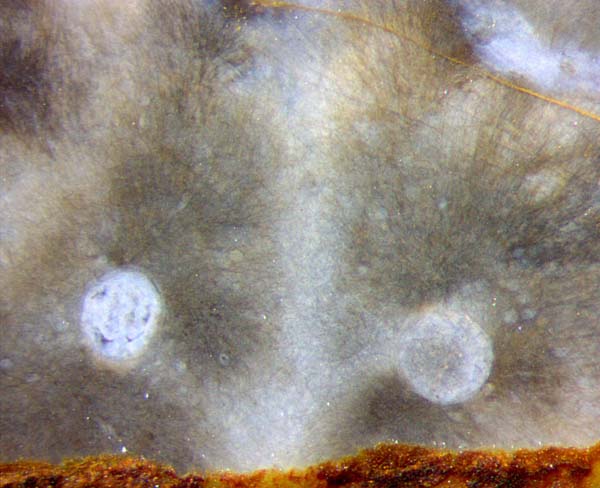

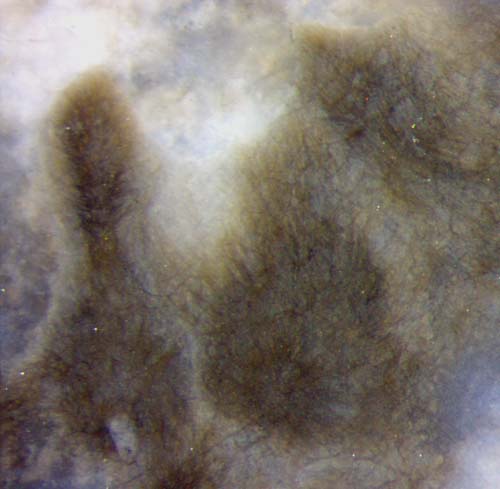

Figs.2 and 3 (smaller one below): Croftalania

tufts on plant cuticle.

Width of the pictures 4.3mm,

0.9mm.

Although Fig.2 is less conspicuous than Fig.1,

it is more instructive. In Fig.1 it is not quite obvious on which

substrate Croftalania had

grown because the agate had formed later in the water-filled cavity.

Inspection of Fig.2 suggests that in Fig.1, too, it had grown

on

the cuticle of a decayed land plant, probably Aglaophyton,

of which only a roughly elliptical shape is left. The instructive

feature in this picture is the thin line detaching from the periphery

in the upper half on the right and dangling loosely inside. It is the

cuticle which had served as the substrate for Croftalania

but is pried loose from it now. (One

should ignore the stained cracks which do not provide any information

here.)

This

configuration permits some conclusions concerning the mechanical

properties of the components. The coating consisting of Croftalania

has preserved the contour of the vanished plant

tissue while the cuticle

was peeled off, hence

it must have been stiff. Such stiffness is compatible with the

assumption that the cyanobacteria filaments were embedded in organic

gel and that all tufts of the coating were fused into a continuous

layer of gel. Patches of the layer broke off, one is now seen still

adhering to the end of the detached cuticle, enlarged in Fig.3, where

the (displaced) cuticle is clearly seen as a thin dark line. If no gel

were

involved

and the filaments were simply dangling in the water, the tufts sticking

to the end of the detached cuticle would probably have become deformed

by

the motion. The absence of

any

visible deformation is another argument for the presence of gel between

the filaments.

Often the tufts show a textured appearance, as expected, owing

to the directed growth of the filaments. The growth is usually

more vigorous upwards to the sunlight, as seen in Fig.1 and in several

pictures of [2].

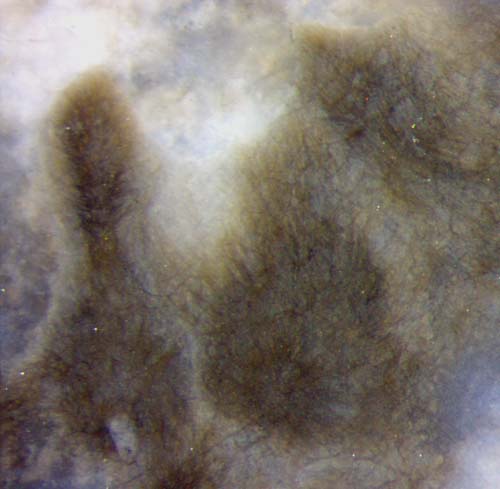

In

the present sample the texture due to growth is often superimposed by

phenomena which might be degrading effects in the organic gel between

and around the filaments. The radial growth direction with respect to

the cylindrical cavities in Fig.4, still faintly seen here,

has

become

overlaid with equally faint lines of other orientation and with small

whitish spots.

Fig.4 (right): Croftalania

grown on unidentified plant parts. The radial arrangement of the

filaments is apparently spoilt by secondary phenomena in the gel. Width

of the picture 2mm.

Fig.5

(left): Croftalania

tufts influenced by shaping after growth and by the formation of a

network of narrow cracks of uncertain cause.

Fig.5

(left): Croftalania

tufts influenced by shaping after growth and by the formation of a

network of narrow cracks of uncertain cause.

Width of the picture 1.4mm.

In the absence of apparent degradation, as in the sample described in

[2], silicification turned both the organic

gel and the surrounding water into

clear chalcedony. The phenomenon of clear substances turning white is

always due to the formation of grains or holes with sizes comparable to

the wavelength of light. Hence, the patches of whitish chalcedony

in the present sample could have been brought about in different ways:

The organic gel itself could have become whitish by degradation, or

substances released in degradation could have triggered crystal growth

during silicification such that the chalcedony became whitish. By the

way, whitish chalcedony improves the visibility of the cyanobacteria

filaments lying near the surface of the chert.

The

club-shaped tufts in Figs.1,5 indicate the action of processes other

than mere growth of filaments. With the presently available fossil

material and facilities, only a minor part of the arising questions can

be answered. The clear-cut outlines of the tufts which do not

correspond to the bunch of aligned filaments, as seen on parts

of

Fig.5 and much more distinctly in [2],

had most probably been shaped by grazing aquatic creatures, an idea

supported by the presence of the crustacean Castracollis on the

"blue-green meadow".

All pictures have been taken from the cut faces of one

chert sample of 0.19 kg obtained in 2014.

H.-J.

Weiss

2015

[1] M. Krings, H. Kerp, H. Hass, T.N.

Taylor, N.

Dotzler:

A filamentous

cyanobacterium showing structured colonial growth from the Early

Devonian Rhynie chert.

Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn.

146(2007), 265-276.

[2] H.-J. Weiss:

Croftalania venusta

and other Lower Devonian microbes. Rhynie Chert

News 56.

[3] H.-J.

Weiss: Rhynie chert -

Implications of new finds. European Palaeobotany and

Palynology Conference 2014, Padua.

|

|

72 |

Fig.5

(left): Croftalania

tufts influenced by shaping after growth and by the formation of a

network of narrow cracks of uncertain cause.

Fig.5

(left): Croftalania

tufts influenced by shaping after growth and by the formation of a

network of narrow cracks of uncertain cause.